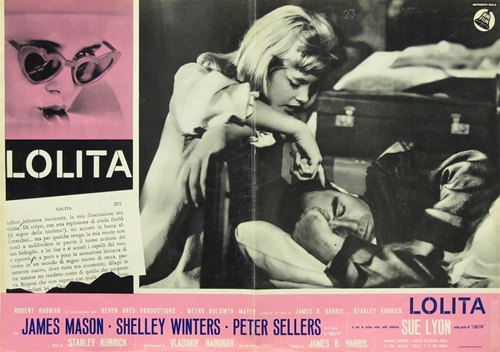

As my entry to The Great Movie Debate blogathon hosted by Citizen Screenings and The Cinematic Packrat I submit this debate on Stanley Kubrick’s LOLITA (1962). Note, before you continue, that I had the nerve to ask Joe of Nitrate Stock to go a round or two with me on this film. If you’re unaware, Joe is as dedicated and knowledgeable a movie fan as there is and his site is a must for anyone in or near New York City as he discusses key film screenings for the classic and repertory fan. This debate, a term I use lightly, may well turn out to be one-sided, but I’m determined to give it a go.

Before we begin, a bit of background information:

When Stanley Kubrick made LOLITA Hollywood was broadening its acceptance of slightly more scandalous stories to be tackled on film. Martin Scorsese said that at a time when American cinema was on its way down, due to the collapse of the studio system, with LOLITA, Kubrick made a film that made people “stop and look” at the possibilities or at what American cinema would become. In that regard Kubrick pushed the envelope with LOLITA, not only by tackling the controversial topic – an older man infatuated with a young girl – but also in the way he filmed it.

LOLITA is appreciated by most today and did well at the box office upon its release, but the film had a terrible distribution problem. The Catholic Church succeeded in holding it back for over six months due to its subject matter. Kubrick had to re-cut the film to make it “acceptable” for release and later said he would have chosen not to do it had he known the limitations that would be placed on him and his film. It’s interesting to consider what the film would have been like had the director been able to make it his way, but as it stands both Joe and I have opinions – and here they are:

Aurora:

While I admire Stanley Kubrick’s penchant for originality and sticking to his guns as far as his art was concerned, I am not necessarily a fan of his films in general. There are a few I think are great, but that’s not the case for all and LOLITA is one of them.

To begin, I think it’s important despite subject matter that the audience identifies with at least one character in a film in some way. You get none of that in LOLITA. Humbert Humbert, the middle-aged professor who’s obsessed with the film’s 14-year-old title character has absolutely no redeeming quality, leaving no chance for anyone to identify with him. While I understand he is a despicable character and that the film deals with pedophilia, which is not a topic to be necessarily understood by most people, the lack of “build-up” in the movie in that regard leaves a flat character arc despite a good performance by James Mason. Humbert starts off as creepy as he ends up even after the long and tiresome journey we are made privy to.

Similarly, Charlotte Hayes, the teenager’s mother, played by Shelley Winters dives right in to the height of annoying desperation as soon as we meet her and only gains ground on a scale of insufferable pathetic in subsequent scenes. Yet again, there’s nowhere to go. We get it in the first few minutes, after which I am always eager for the movie to end.

Having just recently watched PATHS OF GLORY again, I can’t help but compare it with LOLITA as far as efficiency goes. Kubrick succeeds in telling a disturbing story in PATHS in an in-your-face manner that pulls no punches rendering the viewer unable to look away, as I mentioned in my recent commentary on that movie, despite the disturbing nature of the story. That’s what makes PATHS one of, if not THE, greatest of his films in my opinion. With LOLITA Kubrick throws efficiency out the window and makes a tedious movie filled with tedious scenes any number of which go on for far too long. Add the superfluous Clare Quilty (Peter Sellers) scenes, which disrupt the story at every turn allowing for yet another reason for me to turn this thing off. I’m not a fan of Peter Sellers’ brand of weird to begin with so when his Quilty routines, which are how I see them, appear in the movie without reason the best they do is, again, disrupt the story. Every time I watch LOLITA it occurs to me that a 15-minute cautionary PSA would have been more effective.

Joe:

Oh yeah? Well double nyeh on you! And good day madam!

(Slams door!)

Oh there’s a word count? And that wasn’t enough?

Ahem.

First off I’d like to thank my good friend and host Citizen Screen for inviting me to join her for this lively discussion. I found the prospect most inviting not merely because of my debate partner’s cred, but because the film, while the product of one of my fave filmmakers, is also one I find myself regarding the least, though not holding it in the least regard.

LOLITA is a tricky film, as outlined by my colleague’s opening salvo, not a work for every taste. It marks for me the second phase of Kubrick’s career, one where he began to mess with audience’s heads well in advance of the dimming of the lights. As Aurora mentioned, the very selection of the Nabokov novel as suitable screen material was cause for scandal back in the Kennedy era, an atmosphere not merely predicted but provoked by the auteur. It was a practice he would continue for the rest of his career, one in which I draw my own line of demarcation (anything post-CLOCKWORK, that’s the subject for a different blogathon). To be fair, I’ve only ever really compared phases of his career to each other, not so much his individual films. I’ve often compared his 1st phase to his 2nd, but rarely if ever, say, PATHS OF GLORY to LOLITA. While I admit the WWI courtroom procedural is the better film, tighter, surer, I also think, were I to compare the two, that it’s the easier task between them. Yes, there are no likable characters in LOLITA, but PATHS is non-complex, never wavering in its loyalties to one set of characters or its indictment of another. It’s 90 minutes of hissing at the black hats, though granted nobody could hiss quite like Kirk. Effective, yet simplistic by comparison to the much more complicated, savvier, blacker comment on postwar American consumerism, where the object of desire has devolved from the staples of status to debauchery itself. The manicured lawn and the Buick aren’t enough anymore, American virginity itself is the latest must-own.

PATHS OF GLORY is a pristine examination of dignity in the face of dishonor and the dishonorable. LOLITA is about undignified characters made worse by their lusts, their ambitions, their belief in a consequence-free society, the very thing promised by Madison Avenue’s postwar dream factory. Humbert is a pilgrim to this most foreign land, a onetime colony that has grown too mature too quickly, much like the American teenager of the 50’s and 60’s. I don’t think Kubrick is ever on his side, ever promoting of his desire to defile this symbol of New World purity, this hula-hooping Id. I don’t, actually, think he’s on the side of any of the characters in the film. However, while he indulges in black social farce, and actually finds humor in the material (something that would later turn to full-blown humorless misanthropy, hence my post-CLOCKWORK distaste), he allows the characters their humanity, he grants them their moments of suffering. Yes, they’re building their own gallows, and yes the whole purpose of the exercise is to witness, even wallow, in their tragedies, but Kubrick exhibits some compassion for the players in the game. The ingredient perhaps most responsible for this potential empathy is star James Mason, a BIG favorite of mine, in what perhaps might be his finest 2hrs 25. Always excelling (and therefore always typecast) as manhood somehow compromised, whether slapping Judy Garland in A STAR IS BORN or hinting at a very particular type of war wound in 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA (The Nautlius? Must we consult Freud?), he is given perhaps his most emasculated role in LOLITA, the initially smug professor, regarding the crass culture he must endure while on academic business with disdain, ultimately descending not through Hell’s circles, but its hoops. He ultimately is putting on the show for Lolita, not, as he believed, vice versa. He navigates the journey from villain to tragic wretch, maintaining not only our interest but ultimately earning our pity. He’s a miserable figure, from beginning til unbearably so at film’s end, and it was the height of bravery to accept the part, the apex of his talents to retire the jersey on it.

So what say ye, Aurora? Have I swayed you at all?

Aurora:

Pffft!

Hardly, Mr. film scholar! And yes, that’s what you are. I, however, am much more of a casual film viewer, which basically means the movies I watch must offer – first and foremost – entertainment. You explain the merits of LOLITA beautifully, but I’m afraid its value as social commentary is lost on me while I struggle to get through the muck. I’m just not interested in these people or their downward spiral and if that was Kubrick’s intent then kudos. But that disinterest goes far in making me want to step away early in this case. And that disinterest goes for Humbert Humbert most of all. While I agree that Mason portrays the wretch truthfully and bravely, I never pity him if only because he reaches those depths in monotonous disquietude. Let’s move on, I get it! Cut a good 45 minutes from this puppy and I’d still get it. And we get back to excess – inherent in the story and the telling of it as a sign of the times, a message that could have been delivered more effectively without going to cinematic extremes. And by “extremes” I mean among other things, but most conspicuously – what is Peter Sellers doing in this movie?

One other thing, Joe, with regard to the comparison between LOLITA and the far more effective PATHS OF GLORY – I agree with you that a comparison is not merited and I mentioned both only because I saw them in such close proximity so that the difference in efficiency struck me. However, that efficiency warrants another mention now since you so eloquently describe the simplicity of PATHS vs. the complexity of LOLITA. There’s a lesson to be learned for sure. Stanley Kubrick takes us through literal muck in the former, albeit simpler story so that we never doubt the film’s position and revels in the muck of the latter ad nauseam. I’ll take simplicity almost every time, which is why I am not a fan of several of Mr. Kubrick’s later efforts.

Joe:

HARRUMPH, ma’am! No one calls me a film scholar and gets away with it!

Firstly let me correct myself: if I implied that the comparison between PATHS OF GLORY and LOLITA was an improper one, that was not my intent. I only meant to convey that I hadn’t quite considered it before. Indeed, it’s a pretty entertaining and thought-provoking exercise matching the pair, not merely due to their parentage but their emblematic status of their representative eras, separated by a mere 5 years. PATHS is fairly straightforward populist filmmaking, an Eisenhower war flick whose only grey exists between the black and white of the photography. This is no knock by the way: few filmmakers got material this sober and somber this right in execution. No pun intended. As I said, I agree it’s the superior film, but I maintain LOLITA might be the more interesting effort. PATHS ends tragically, with a slim glimmer of humanity fanned, the ability of the frightened tavern girl to crack the hard hearts of the raucous, weathered soldiers with her trembling warble. Indeed, in this scene Kubrick first displays a propensity for conflating an assemblage of unappealing faces and behavior with humanity’s enduring ugliness, something he’d soon and routinely overindulge, and that Woody Allen would be criticized for on multiple occasions much later.

Aurora:

By “soon overindulge” I say…you’re not kidding! There’s little else but humanity’s enduring ugliness in LOLITA, as far as I’m concerned. Interesting effort? Perhaps. I certainly recognize the gall it took for any filmmaker to have taken on this particular subject, one that would still be a difficult one to tackle today. So I do give Kubrick his due for being a nonconformist, which is what I most admire about his career despite the fact that I am not a fan of much of his work. I most definitely respect the artist.

On the statement you make regarding the “populist” PATHS vs. LOLITA, I will concede that the subject matter in LOLITA is inherently distasteful so the fact I want to continually look away, versus being rendered unable to in PATHS, is understandable. Or, not necessarily due to how the story is told, which is what I have a problem with.

Joe (cont.):

LOLITA, by comparison, ends tragically with a sad excuse for humanity, Humbert’s decision to leave his stepdaughter/”succubus” with the entirety of the estate, and the remainder of his equity as well. It’s by no means redemptive of his callow and callous decision-making and behavior, which has brought ruin to him, but it does show that perhaps his only virtue, albeit misguided, remains intact: his devotion. Nor is Sue Lyons’ nymphet concluded as soulless Harpie, instead afforded a short moment of exposition, of clumsy explanation. It’s a scene and an act that remains cringe-worthy to this day, for more than a couple of reasons, yet that alone may be enough cause to champion it, and it stands in harsh contrast to later films Kubrick would make, wherein the participants were regarded with and afforded no empathy whatsoever.

Aurora:

I don’t see Humbert’s final purge, as a manifestation of any kind of devotion, but I get what you mean. As far as Lolita and Lyon’s portrayal – probably due to a “softening” of the character due to censorship issues, she never quite comes across as anything but a figure important in order to realize Humbert’s perversion. Lolita ends up with as “normal” a life as one would expect/want someone of such a young age to end up – with the prospect of a “normal” future in any case, which is where I go regarding this character. That is, if I cared enough to think of any these people as having a future. I am never that invested in them.

Joe:

I have to say I do find certain works of cinema, ones that showcase not merely anti-heroes but persons damn near irredeemable, as close as lead characters can be to worthless but whose story retains worth enough for the telling, when well-motivated and executed, to be fascinating fare. As such LOLITA shares shelf space with Scorsese’s RAGING BULL and Allen’s BLUE JASMINE, films that do not excuse the actions of the truly wretched yet still ask the audience to spare some sympathy, even empathy. It’s a dare: how far can I take you down this person’s pilgrimage to hell while still asking you to see some part of your own weakness within them. Humbert is indeed despicable, yet I appreciate the Kubrick adap, perhaps unfairly in contrast to his later, crueler focus. As much bleak and black humor as he derives from the proceedings it might be the last time he saw enough awful fragility within himself to spare his bad actors some, dare I say, mercy?

Aurora:

There’s a lot of interesting psychology in your statements there. I take my hat off to you, Joe – I can’t even go there with this one. I will add, however, that I find your mention of both BLUE JASMINE and RAGING BULL interesting and valuable from a character perspective. From the storytelling one I want to point out a difference that gets to the center of my problem with LOLITA. That is that both Scorsese and Allen allow for respite from the depth of despair in the main characters. I feel sympathy for both of those main characters, while I can summon none for Humbert. Go figure.

ALTHOUGH, if I were allowed an uninterrupted story ie. sans Quilty then who knows?

JOE (cont.):

Which brings me to Clare Quilty, and Peter Sellers. I find him not only not superfluous, but crucial to the twisted morality play at hand. He is both the product of Humbert’s sins, a quizzling imp perfectly at home in this plastic amoral wasteland,

and the hot poker prodding what’s left of the aloof linguist’s conscience. He is the worst manifestation of this manufactured New World, with all its decadence and disingenuousness and deceptiveness. If this is modern myth he is Loki, the trickster, come to a land even more equipped to avail his worst tendencies, except he is properly placed to torment a lead character most decidedly un-Thor. If Humbert pretends to any proprietary panoply, and thinks this sufficient replacement for his lapsed morality, Quilty is never far behind, literally, seemingly conjured to disabuse this sinner of his delusions. A case could even be made, I’m sure, that Quilty doesn’t even exist beyond Humbert’s paltry, putrid imagination, that he is indeed the ethereal manifestation of his self-hatred, a Tyler Durden from the birth of post-modern culture, one also none too beloved or beloving of his inadequate host self. Except he is corporeal, not absolute devil, as evidenced by his ultimate mortality, unless you view this final act as provoked suicide, last nail driven in Humbert’s coffin, purpose fulfilled. But I think the point of their dynamic is thus; even a minor devil can be raised to major status. Provided the sin is great enough.

Aurora:

Although you’re too open-minded to do so, I’ve been told I’m crazy in the past for not enjoying Sellers’ stint as Quilty in LOLITA one iota. You make some great points, though and I will admit that it has occurred to me – on occasion – that Quilty is indeed a manifestation of Humbert’s alter ego or the part of himself he despises most. The thought came as I tried to overcome the “what the hell is this?” annoyance I feel at watching those scenes. I’m not saying you’re saying I’m clueless, but I may well be in all matter of things that fall well outside my comfort zone and this may be one of them. But, that view of Quilty – as being a “part” of Humbert – is one I retreat from because I cannot get past the indulgence. In fact, it’s personally insulting on some level. Is that strange?

Joe:

But fair play: if you see nothing more than terrible human beings, that’s exactly what’s on display. And I’m not condescendingly implying I’m privy to deeper levels of the film than you might be. All art is subjective, and by all means there are tens of thousands of stories with far more redeemable characters to award your sympathies. How ’bout this: let’s widen the compare/contrast to Kubrick’s entire CV and then cinema in general. Whatsezye?

Aurora:

It is subjective and you’ve certainly given me lots to think about. It’ll be a while before I revisit LOLITA, however. A cleansing of the cinematic palette is in order. And, if I haven’t bored you to tears I’d really enjoy the task you’ve set before me. Let’s continue the debate as you suggest and see what happens.

I can’t thank you enough, Joe for taking the time to do this. It’s been a blast.

Joe:

Becketchya Bebeh! I never get tired of talking film, and it was an interesting task championing a film I deem important yet flawed, against an opposing POV that considers it a post-modern meh. Each argument carries equal ballast methinks, and I think we’ve utilized said jumping off points to concoct a dialogue worthy of interest. Now let’s see if the comments section proves me right. Thanks again, and what are we discussing next?

♦

Love that enthusiasm and I hope you enjoyed this debate. Joe and I may be back with more opinions, but for now this one’s for The Great Movie Debate blogathon hosted by Citizen Screenings and The Cinematic Packrat. Please be sure to visit the host sites for more arguments for and against notable films.

Lively! I love this sort of thing, well done! Very good jousting!

Well, I disagree that films need to be entertaining, and I don’t believe that we must identify with anyone on screen; movies, like any experience, are also there to challenge us, to teach us, to give us opportunities to see things through other eyes. This one is prime for that, as these type of people, while doing something morally repugnant in the current sociopolitical context, they are still people, and outside this sexual aspect, are indistinguishable from anyone else. In older days, things were different; my grandfather was almost 30 when he married my 14 year old grandmother; it was just after WWI, and these things were not unknown by any means. It challenges the concept of acceptability to see this sort of attraction put in a context in which it is no longer acceptable.

Honestly, while I think this version does a good job, the later version with Jeremy Irons opens the wormcan to a greater degree, as the Lolita character is played by a very attractive actress. I remember a co-worker, very liberal and proper, having just seen the film in the theatre, leaned in with an uncomfortable look on his face and said, “…is it wrong that I was attracted to her?”.

That said it all about the story to me; it’s a window into a person like you and me, but a person who has what is currently considered a problem. It’s important, I believe. 150 years ago it would not have been an issue in most places, yet, say, homosexuality would have been mostly reviled…now the opposite is true.

It’s good to have these challenges…thinking never hurt nobody. 🙂

Thanks, Clayton. I do need to be entertained, relate or identify or SOMETHING that allows some kind of connection. LOLITA simply doesn’t do it for me in any way, shape or form. But, this was a hell of a lot of fun. And there is merit even in negative emotions a film may evoke. Story is important to me too, but this one – well, I said all I had to say about it. THANKS for stopping in and your great comments.

Aurora

Wow you took this is a terrific read!! Well done!

You two is what I meant. Oops. Sorry.

Ooh, a fight, a fight!

Nice post, you two. Not a knockout in those rounds against each other, but a case for liking and disliking a film I’ve always felt wasn’t meant to be “loved” in the first place. For me, it was a button-pusher for America in it’s still kind of puritanical early 60’s stage that’s arty in a way, yet timely (well, for the time it was made). I’d actually compare it to Kubrick’s final film (that which shall not be named because it’s got the most annoyingly narcissistic actors cast as leads (playing themselves?) and is a complete pain to watch, even the non-CG-fested uncut version), because it has some of the same themes running through it. Lolita wins that match for me, but it’s not a film I’d dig out to show to people as a “winner” of all that much.

That said, I like the Jeremy Irons version better because you got a more sym-pathetic creep to watch, but not feel sorry for by the finale. Every character in both versions is twisted in some way and I’ve always seen the story as more of an “Oh well… these sort of people DO exist…” tale than one that needs to have likable characters or even unlikable ones with better things going for them. As a counterpoint, I’ve always disliked Gone With the WInd because NONE of it’s main characters are all that smart or likable and the audience has to deal with their stupidity while letting the “romance” pretty much save them from leaving the theater if they set aside enough time to think about things from a more normal perspective.

And what, no love for Barry Lyndon, Mr. Joe? Okay, I’ll let that go. I didn’t like it until then third time I saw it (and managed to stay awake until the ending).

Thanks, geelw! I agree LOLITA is not a movie that anyone should necessary loved. As I mentioned above, I just need breaks from films that wallow in muck and that’s what this one does to me. Even if those breaks in in my own mind. Interesting to compare this one with that other one that shall remain nameless – that one I hate because it’s just a terrible movie to me. While I dislike LOLITA and find it difficult to get through it, I still understand other people liking it. That’s not the case with that other one. As for your comments on GWTW – want to debate that one some time??? 😀

Aurora

Oh, don’t get me wrong, GWTW is a GREAT film, but I’ve never liked it other than for the visual impact. I think Scarlett got on my nerves and Rhett was more of a jerk than even she deserved. Well, I suppose I can watch it one or two more times and take some notes. It’s certainly a film that stands up to repeat views.

And yup, that film that shall not be named IS terrible. I actually need to sit through it one more time with a friend who’s never seen it but wants to just to complete his Kubrick cycle. Why he couldn’t have gone backwards or sideways is beyond me, but maybe I’ll sneak in A.I. just because it was supposed to be a Kubrick project and Spielberg at least made it look like one (although I don’t like it all that much)…

What a fun post to read! Bravo, you two. I personally love Kubrick–all his films–and while the book by Nabokov is infinitely better than the film version, I thought the acting was fantastic.

Great post! I’ve never seen any version of this film, or read the book, and you’ve got me intrigued. I’ll keep this post handy as a reference if I do see the film… It’ll be like a Bonus Feature on a DVD!

Great debate. Doubt I’ll ever watch Lolita. Too far outside my comfort zone.

Throroughly enjoyable read. I have felt the same responses from time to time about this film, and often vacillate between your two opinions. A great idea for two fabulous cinephiles!

Great post and a lively debate! I don’t have a fully formed opinion on Lolita as I’ve never seen the film in its entirety, but from what I’ve seen, I too feel like Kubrick wasn’t making a provocative film that was meant to be liked (although his version is considerably tamer than Nabokov’s novel!). I do find some of the scenes quite laboured – the one where Sellers impersonates the villain for example – but it’s redeemed by Kubrick’s power of suggestion, the innuendo and clever staging that attempted to get round the censors.

* I mean, he WAS making a provocative film (it’s been a long day!)

Wonderful post – great food for thought. I think I come down on the side of “Lolita” but barely. Kubrick knew we people in the dark were all voyeurs at heart.

I’m entering the discussion months after the fact, so I doubt anyone will read this. But Humbert’s narrative is the ultimate solipsism anyway, so…

While I heartily enjoyed the debate, kudos and bravos to you both, I have a problem with all the Lolitas and most discussions about them. My father was a pedophile, and Kubrick’s Lolita, when it was released in 1962, was a stimulus for him to act out his impulses. No, the movie didn’t create his prurient tendencies, but it legitimized them and planted the idea that, at age 14 (the same as actress Sue Lyons) I was a suitable romantic projection, as were two other teens he preyed on.

Granted, I’m biased. But intelligent and sincere as this debate is, like so many others on this subject, it seems to suffer from massive doses of dissociation. It is like the old quip, “Aside from that, Mrs. Lincoln, how did you like the play?” Society is in denial when it comes to the real Lolita — which I believe is an intrinsic consequence of the nature and structure of the novel. When I read the book in 1968 as a junior in college, my (male) professor treated it as an academic exercise, analyzing the literary merits without any mention of pedophilia, or a shred of compassion for the 12 year old child. Perhaps that is what Nabokov intended, because in some respects we are still there today.

Of the three versions, I prefer the novel — which ironically triggered my abusive memory five years after the fact. Prior to reading Lolita I was in a total blackout about my father’s behavior, did not remember the incident whatsoever. Sexual abuse was off the radar then, and like many girls in my day, I had never heard of pedophilia or imagined that a grown man would want sex with an adolescent. (In this respect, times have changed for the better.)

I have to admit I admire Nabokov’s brilliant use of language, and more importantly, appreciate that he offered glimpses of Lolita’s very real suffering, showing her plight as an orphaned sex captive, her loneliness, and the impact the exploitation had on her –all of which may have triggered my own incestuous memory. But at the same time, I sense that part of Nabokov himself was the prurient, hyper intellectual, and therefore emotionally dissociated professor he creates in Humbert. In interviews after the book was published, he professed compassion for the character he called “my little girl”, yet he, too, used her. I don’t believe the author who created Lolita had any real concern for her welfare, or for children like her…in his mind, she was an allegorical symbol, a means to make an intellectual point, perhaps about American society, perhaps about human nature…No one seems to know, as he was cagey about his intentions. It has been said that his wife was the one who urged him to show crumbs of Lolita’s emotional reality. We catch glimpses of the girl’s suffering through cracks in the prose of the quintessential unreliable narrator — a pedophile facing criminal charges who sees the child as a temptress. I believe the nuance her feelings provide accounts for the novel’s greatness, the way shadows and perspective elevate a drawing from two to three dimensions.

Kubrick’s film is more disturbing to me, not that it is without merits, because those very feelings have for the most part been deleted. Here Humbert is whitewashed, made suave, less pathological, his disintegrating mental state far less obvious. The mother, played by Shelly Winters, is exaggerated in the other direction, we mildly despise her, with the result that Humbert appears the more sympathetic by comparison. Significantly, Lolita’s age was raised from 12 to 14, not just for the censors I would argue, but to bypass the censor in all of us — better known as empathy and conscience — thereby coaxing the audience to taste forbidden fruit within the safety of a familiar equation: big breasts equals grown woman (whereas Nabokov’s nymphet, just budding, was specifically a child).

By the way, according to the Life magazine article that appeared in May, 1962, just before the Kubrick movie premiered, Nabokov stated unequivocally that he would never write the screenplay, that to conjure Lolita in his mind was one thing, but to portray her with actors in a movie would be “a sin”. Apparently when Kubrick offered him the job, he caved and not only scribed the film, but gave himself a walk-on cameo. Reportedly, only 20 percent of Nabokov’s script was used.

Adrian Lyn’s version of the story is in my opinion pathetic and despicable for the simple reason that, by the 1990’s, he and his financial backers should have known better. When his movie aired on Showtime, the channel’s website advertised “thrills” and called it a “journey to paradise lit by hell’s flames”. Those words came directly from the novel (in other words, from the mouth of Humbert the pedophile), and were used to titillate the public and thereby sell the film’. For me, the exploitive intent is evident throughout.

The venture was a costly miscalculation. After a spate of high profile sexual abuse cases, society’s eyes were open to the devastating costs and prevalence of pedophilia, and the movie went down in its own flames, a financial bomb of epic proportions. Rightly so.

As a survivor who has suffered the long term costs, it is impossible for me to enjoy Lolita as a rollicking man-child sex romp, or to ignore the titillating subtext that lies at the core of all three versions, or deny for a moment the effect on the child.

lolita was great. A masterpiece. Watch it again and you’ll see.