On July 10, 1925 John Scopes, a twenty-four-year old general biology teacher and part-time football coach walked into the Rhea County Courthouse in Dayton, Tennessee charged with illegally teaching the theory of evolution. Although the Scopes Trial would be known in association with his name the “crime” he was charged with would in essence take a backseat to what the trial would become – a war between traditionalist moralists and progressive modernists, social versus intellectual values all set on a stage on which men could extend their moments in the limelight.

“Scopes was being used. He was completely willing to be used. But essentially the case had been taken over by the big names.” – Kevin Tierney, Historian

The Scopes “Monkey Trial” as it would commonly be referred to was the first trial ever to be broadcast live, a virtual circus replete with interesting players, the least of which in many ways was John Scopes who’d broken the law when he used the state-approved textbook, Hunter’s Civic Biology and its lesson on evolution. The main player for the prosecution’s side of the argument was William Jennings Bryan, a three-time candidate for President who was already leading a fundamentalist crusade to banish Darwin’s theory of evolution from American classrooms. Viewed as an advocate for the common man, Bryan’s argument that Darwin’s theory undermined traditional values kept him in the public eye making him a natural to lead the crusade to introduce legislation in fifteen states to ban the teaching of evolution. As such, most in Dayton, Tennessee were thrilled to have William Jennings Bryan defend their values and their Bible on what was an increasingly large stage.

When it came to the defense several notable names in politics and law came forward to volunteer, some making the trek to Dayton for the opportunity to be a player in the trial of the century. But, regardless of the worries of many in the ultra conservative South, it was a zealous agnostic, almost seventy-year-old Clarence Darrow who hadn’t practiced law in over thirty years that got to lead the defense team. Darrow jumped at the chance  the moment he heard Bryan would prosecute the case. He had a passion for defending the underdog and remained the country’s most famous defense attorney.

the moment he heard Bryan would prosecute the case. He had a passion for defending the underdog and remained the country’s most famous defense attorney.

Once the players were set the carnival atmosphere that permeated all walks of life in Dayton only broadened. Banners decorated the streets, Chimpanzees, said to have been brought to town to testify for the prosecution, performed on Main Street and preachers could be heard reminding everyone of the true meaning of scripture at every turn.

Nearly 1,000 people crammed the courtroom on the first day of the Scopes trial. The place was so crowded that the presiding judge proposed moving it to a tent where 20,000 could be accommodated. Every single utterance of such nonsense played into the hands of the media who was chomping at the bits for such an ordeal.

The proceedings opened, over Clarence Darrow’s objections, to a prayer, the basis for the entire case for the prosecution which argued that “if evolution wins, Christianity loses.” Such words by Bryan would often be followed by “Amens” from the crowd who supported the fundamentalist views. These outbursts served to strengthen Darrow’s case in the eyes of the world outside of Dayton, Tennessee, “Scopes isn’t on trial; civilization is on trial.”

And so, the real-life drama began, an eight-day trial that didn’t disappoint anyone. The players were in the spotlight as was the town of Dayton who suddenly had the eyes and ears of the world on Main Street, its voices echoing throughout the country by way of print, radio and Hollywood newsreels. The media feasted, particularly journalist and essayist, H. L. Mencken from Baltimore, who was already prone to writing scathing essays about the American South and its views. Mencken covered the Scopes trial as satire and is the one responsible for dubbing it the “Monkey Trial.” If you’re familiar with this story whether by way of history, theater or the movies you’ll note that the real life circumstances were dramatic, ripe for the stage and screen adaptations. Although John Scopes himself, as he would note in his 1967 biography, “Center of the Storm” thought real-life more dramatic than fiction, “A man’s fate, shaped by heredity and environment and an occasional accident,” he wrote, “is often stranger than anything the imagination may produce.”

◊

“He who troubleth his own house shall inherit the wind.” – Proverbs, 11:29.

On April 21, 1955 a young actor named Karl Light stepped onto the stage at the National Theatre in New York on opening night of the much-anticipated production of Inherit the Wind, a play written by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee based on the Scopes Monkey Trial three decades earlier. Light was portraying Bertram Cates, a science teacher on trial for teaching evolution in a school in the South. Although he played the accused, an important role in any courtroom drama, as in the case with the real-life teacher his character was based on, the drama didn’t revolve around him, but rather on the two actors playing the heavy-hitting attorneys involved in the case. Those actors were veterans Paul Muni who came out of retirement to portray the Darrow-inspired Henry Drummond and Ed Begley as the counterpart to Bryan, Matthew Harrison Brady. The part of the cynical, Baltimore journalist, E. K. Hornbeck was played by Tony Randall.

The Broadway production of Inherit the Wind was a huge success, in part due to the relevance of its theme during a time when the country was experiencing the anti-Communist sentiment of the McCarthy era with personal rights and freedoms questioned continuously. The play’s producer-director, Herman Shumlin was able to capitalize on the theme and the fact the play had been a success in Dallas to gather the stellar cast for New York, particularly the legendary Paul Muni as the playwrights noted,

“One day Muni took us aside, and said, ‘Boys, I didn’t do this play because I want to see my name in lights. I’ve had that. I didn’t do it because I needed the money or wanted to show off.’ Then his voice became soft. ‘I did it because I liked the words.’ Can any playwrights ever hope for higher hosannas? Needless to say, we are two very happy writers. For seeing Muni is an experience. Working with Muni is a delight. Knowing Muni is an inspiration “

Inherit the Wind was Paul Muni’s biggest stage success on the American theater with his portrayal of Henry Drummond earning him the Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Play. That production would also earn Tony Awards for Ed Begley as Supporting Actor as well as scenic designer Peter Larkin.

Despite its successes, however, Inherit the Wind had detractors, arguments questioning the play’s historic accuracy. I have to assume that it is due to the naysayers who viewed the play as a misrepresentation of the 1925 proceedings that every official ad for the original 1955 production includes a statement about the fact in one way or another.

“Inherit the Wind is not history. The events which took place in Dayton, Tennessee, during the scorching July of 1925 are clearly the genesis of this play. It has, however, an exodus entirely its own.

Only a handful of phrases have been taken from the actual transcript of the famous Scopes Trial. Some of the characters of the play are related to the colorful figures in that battle of giants; but they have life and language of their own – and, therefore, names of their own.” – Lawrence and Lee

Based on notes and commentaries made by the playwrights it is clear that they never intended their play to be a historically accurate account of the Scopes trial although some others who had a vested interest in the play wanted to market it as such. Lawrence and Lee not only changed the names of places and characters, but they included several fictional characters into the work, including a fundamentalist preacher and his daughter, who in the play is the fiancé of John Scopes. I find how much Lawrence and Lee actually did include from the Scopes trial much more interesting. For instance, Darrow’s condemnation of anti-intellectualism, which is a powerful speech is incorporated into the play as is an exchange between Darrow and the real-life judge in the case, Raulston that earned Darrow a contempt citation, and portions of the Darrow examination of Bryan are lifted nearly verbatim from the actual trial transcript. (Versions of these would also be used effectively in the 1960 film version.)

In the long run none of that matters, however, because no one can deny that Inherit the Wind made an impact and its (mostly) stellar reviews and audience enthusiasm resulted in a two-year run and 806 performances. The 1955 production proved as memorable a stage drama as its big screen adaptation would prove to be an effective retelling of the story in its own right five years later.

◊

Released by United Artists in 1960, Stanley Kramer‘s INHERIT THE WIND premiered in Dayton, Tennessee on July 21, a day the town declared “Scopes Trial Day” thirty-five years after John Scopes walked into the Rhea County Courthouse as the accused. Gone were the “Read Your Bible” signs on Main Street replaced with “Welcome to Dayton Scopes Trial Day July 21” hoping to shine the spotlight on Dayton once again. And it did for a little while with the story appearing in publications across the country due to the film’s release, a film that in some ways reflects a different society than even the Broadway production, which premiered only five years earlier. By 1960 anti-Communist paranoia had declined substantially and had been replaced by the growing unease of Civil Rights concerns, but there was also a sense of hope.

While Kramer’s movie was a critical success there was discussion as to why certain aspects of the story were “Hollywoodized” similar complaints as plagued the stage version with regards to historic accuracy with added dramatizations to fit the silver screen. I’ll mention a couple of them in a bit, but these are easily explained due to the different climate in the country that occurred within the five-year span – and, of course, due to the medium – the movies are Hollywood more often than not. Why people are surprised by that is puzzling. Still, I make no excuse and most would agree – as entertainment, as a film that features fantastic performances and that tells a compelling story INHERIT THE WIND is still praised and rightfully so. With a screenplay written by Nathan Douglas (aka Nedrick Young) and Harold Smith this is one of my all-time favorite movies, certainly one of the all-time great courtroom dramas. INHERIT, if I may say, is also responsible for my falling in love with Spencer Tracy‘s talent, which in this case is pitted perfectly against Fredric March‘s – Tracy’s signature naturalistic portrayal of Henry Drummond opposite the appropriate theatrics of March as Matthew Harrison Brady make for a true battle of the titans. The most compelling and entertaining scenes in the film are the ones during which these two characters/actors spar. Not only are the characters exciting to watch because they are men well past their prime making (in a sense) a last-ditch effort to leave a mark, but so are the veteran actors who prove that in the twilight of their incredible careers they’ve still got it!

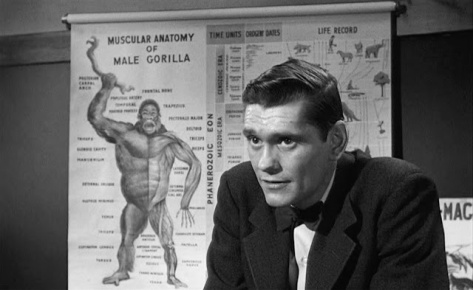

By now you know the story even if you haven’t seen INHERIT THE WIND so I don’t intend to recount it other than to mention that Bertram Cates, in this version played by Dick York in his final feature film, is the young science teacher on trial for teaching Darwinism in a Hillsboro Public School. But, as was the case in the real-life story of John Scopes, the case against Cates merely serves to bring forth all other matters – the law itself, which is really what’s on trial, religious zealotry, a last hope for fame for a man desperate for adulation, another who is out to prove truth outshines spectacle, the frenzy of the media and a town eager to be noticed.

As media outlets across the country start covering the “Monkey Trial” even before it begins, Hillsboro’s allegiance to its beliefs reaches a fevered state fed by one Matthew Harrison Brady, a former politician and self-professed “man of the people” who volunteers to lead the case for the prosecution. Brady is given a welcome fit for a king with a parade and all the ballyhoo the town of Hillsboro can muster. They even make him an honorary Colonel in the state’s militia. Brady is to be the voice of God, the voice of the righteous who live by sacrifice to ensure scripture is realized – literally. Of course the welcome scene alone dispels what they claim to believe in, the puritanical values they hold so dear.

In contrast, Brady’s opponent Henry Drummond enters the carnival atmosphere in Hillsboro on a rickety bus to no fanfare whatsoever. Drummond is welcomed by journalist E. K. Hornbeck (played by Gene Kelly who also delivers a terrific performance) with a sly “Hello, Devil. Welcome to Hell.” The famed lawyer knows what to expect and doesn’t bat an eye at Hornbeck’s attitude or the craziness that surrounds as he steps off the bus. There are bands playing, carnival stands with chimpanzees performing – you name it. Also notable as Drummond arrives in Hillsboro is his determination and seriousness. He’s there to do a job, a stalwart figure supported by the cynical E. K. Hornbeck who is central to all the happenings in Hillsboro, the representative of the press playing judge and jury from his perspective to share with the rest of the country. We get a sense of these characters in mere moments. They are supporters in each other’s “causes,” but not in allegiance on a moral/ethical level. No one, in fact, would be on the same page in that regard as Hornbeck, whose cynicism serves as a kind of balance for the “truth” as it plays out for the opposing sides. He is a man “admired for his detestability,” but what he represents is vitally important.

As far as the rest of the film’s cast it’s a terrific lot of supporting players. Harry Morgan plays Judge Coffey who presides over the trial. The imposing Claude Akins gives an affecting performance as Reverend Jeremiah Brown as does Donna Anderson who plays his daughter, Rachel who is also Bertram Cates’ fiance in the movie. The versatile Hope Summers plays the righteous voice of the people of Hillsboro and Florence Eldridge plays Mrs. Brady who serves to humanize her husband. Elliott Reid, who I’ve seen in a host of classic television shows is co-council for the prosecution here, another attorney interested in the limelight, Norman Fell plays a radio technician in the courtroom and there are plenty of other familiar faces in the town of Hillsboro. You can take a look at the entire cast and crew list here.

I must also mention that INHERIT THE WIND features beautiful photography thanks to the talent of Ernest Laszlo who received one of the movie’s four Oscar nominations for Best Cinematography, Black and White. The shots in the film, whether tight close-ups during the heat of battle or wide shots illustrating the circus atmosphere in Hillsboro are incredibly layered. The other Oscar nods received by INHERIT THE WIND were Spencer Tracy’s nod for Best Actor in a Leading Role, Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium for Nedrick Young and Harold Jacob Smith and finally, Best Film Editing for Frederic Knudtson.

Now on to some of the differences in this “Hollywoodized” version of the “Monkey Trial” story. The first concerns the character of Bertram Cates who is a major player in the film. The teacher’s romance with Rachel Brown is given particular attention in Kramer’s INHERIT THE WIND. As the daughter of the Reverend, the primary religious zealot in the story, Rachel’s involvement with Cates is central to the conflict between thought and faith. Both the love interest and making the Reverend a fanatic allow for not only changes in the other characters, but also guarantee that the story has a wider appeal. For instance, the romantic relationship adds elements to the movie that make it more than just a straight courtroom drama, which likely appeals to younger audiences, a respite (if you will) for those not likely to sit through two hours of messaging.

In kind, making Reverend Brown the zealot from the beginning leaves the door open to showcase a real friendship between Drummond and Brady outside of the confines of the courtroom, adding layers to the character of Henry Drummond and deepening the drama when he is called upon to “destroy” a friend he not only admires, but has affection for. INHERIT THE WIND goes as far as showing that the adversaries have similar personal ideologies. This is in stark contrast to Darrow and Bryan in reality and (as is my understanding) in the stage version of Inherit the Wind. While it seems Darrow and Bryan may have shared a mutual, adversarial admiration, they were not friends and their beliefs were as far apart as could be. The fact that in the movie version the two titan lawyers have a long-standing friendship – two friends torn apart, one by progress and the other by standing still – actually makes the character of Henry Drummond more heroic, a man who stands up for what he believes no matter the cost. It also softens the Brady character by showcasing his vulnerabilities and unlike the Reverend who demonstrates his zealotry with equal vigor from the beginning of the picture, Brady is allowed to demonstrate his excess in that regard as the courtroom drama unfolds.

Despite having seen INHERIT THE WIND numerous times I am transfixed from the opening credits, one of the great opening sequences in film. As the voice of Leslie Uggams is heard singing the gospel song, “Old-Time Religion” set to the beating of a drum you watch a very serious-looking man step down from the steps of the Hillsboro Courthouse and head across Main Street. The man marches with purpose as if on his way to the gallows picking up the judgment posse along the way. As they meet they even pause to synchronize their watches. It’s an opening reminiscent of a classic Western, which sets the stage perfectly for what is to follow – part drama, part circus – as the men end up in Bertram Cates’ classroom just as he pulls down an illustration of the descent of man.

Immediately following Bertram Cates’ arrest (by way of outstanding editing) we are made privy to a town meeting where newspapers from all over the country making fun of the “Monkey Trial” are being discussed – with outrage. “Heavenly Hillsboro, does it have a hole in its head or its head in a hole?” In a beautifully written exposition scene we get all of the contrasting perspectives that will play a role in the drama to follow – that headline represents the cynicism of the media. Then we see Reverend Brown who stands up to remind everyone that Hillsboro must stand strong to fight the Lord’s battle. Now we know what the fundamentalist side thinks. And finally, the town banker stands up to remind everyone that he won’t invest in antiquity, nor will anyone else invest in Hillsboro’s future if the “Monkey Trail” goes forward. He warns that colleges in other states will refuse students from Tennessee who will view the anti-evolution law as an outright affront to thought and progress. And now we know what the modernists think.

As effective as the opening I described is in the film it must be noted that it is perhaps the most obvious dramatization as compared to how things in the Scopes trial actually happened. John Scopes was never arrested in such a fashion (nor was he jailed for his crime). The powers that be in Dayton, Tennessee never walked into his classroom as he was teaching evolution. Instead, and quite undramatically, Scopes agreed to be the representative of “the evolution side” after Tennessee passed a law making it a crime to teach evolution in public schools. A then new organization called the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) responded immediately by placing an ad inviting a teacher to help test the law in the courts. John Scopes was that teacher. The decision would change his life forever and would inspire great works of stage and screen.

◊

INHERIT THE WIND has enjoyed many incarnations throughout the years with stage and small screen productions that have starred the likes of Melvyn Douglas, Ed Begley (who revised his original Brady role in 1965,) Kirk Douglas, Jason Robards, George C. Scott and Jack Lemmon. An impressive lot of powerhouse actors surely drawn to the scope of this story, one based on arguments that are still relevant – ninety years after the actual events occurred and almost sixty years after the original Broadway production opened. Still a respected work, the themes of Inherit the Wind are universal and the drama a compelling one to watch. In fact, our society is still debating the issue of evolution and religious doctrine is still heralded as science by many. We will likely recognize characters in Inherit the Wind as long as we exist – or until we evolve.

The different sides of the arguments in INHERIT THE WIND are offered with varying degrees of conviction, which in the end leads one to conclude that there is at least one truth – we are thinking beings and as such should accept that others think as well. That is after all what’s on trial – the right to think – as basic a concept as anyone can conceive, yet to the dangerous, all-or-nothing mentality it is inconceivable.

◊

This post is my entry to The Stage to Screen Blogathon hosted by The Rosebud Cinema and Rachel’s Theatre Reviews. I’m as excited as ever to read the entries submitted to this event, a great topic for a blogathon and I encourage you to visit the host sites as well to access the other entries, a terrific list.

Terrific review. Must see the film again.Tracy and March sensational.

Thanks, Vienna! Never tire of this one. They are spectacular.

Aurora

I am a sucker for a good courtroom drama and INHERIT THE WIND is one of the finest. I’m not concerned about its historical accuracy nor “Hollywoodization.” It’s just terrific drama superbly acted. The Jack Lemmon version ain’t bad either.

Jack Lemmon can do no wrong with any role. What an actor!! And I agree with you, Rick, on all the rest. Nearly all I read about both the play & movie mentioned the accuracy, which as far as I’m concerned is nonsense where entertainment is concerned.

Aurora

What an interesting essay. I haven’t seen this film in years and think I need to introduce my daughter to it. As you say, it’s still a relevant discussion. Thanks again for all the different angles of research.

Hey, Caren! Yeah, it’s unlikely to get old since in many ways we don’t move forward. Aside from that the performances! MON DIEU!! 🙂

Aurora

I was in awe while watching the movie, but I’m even more now reading your essay. It’s marvelous!

I knew a bit about the real events, but nothing about the play. It’d be a dream seeing Muni on the stage!

I also found out that the movie (and the trial) opened on my birthday! Oh, gee!

Bravo!!!

Don’t forget to read my contribution to the blogathon! 🙂

Kisses!

http://criticaretro.blogspot.com.br/2014/10/variacoes-sobre-um-mesmo-tema-o-passaro.html

A wonderful essay on a magnificent film! It’s one of the great courtroom dramas of all time, along with “Anatomy of a Murder”, “Judgment at Nuremberg”, and “Witness for the Prosecution”.