I grew up watching the films of the 1940s. Those were the ones that were on Television regularly and the productions that remain my movie comfort food. Until as recently as say five years ago what I knew well of 1930s films was little more than the Astaire/Rogers pairings, Warner Brothers gangsters, The Thin Man movies and Universal horror pictures, which were also staples during my formative years. It really wasn’t until I became active on social media, after connecting with other classic movie fans that I really became curious about other 1930s movies. That’s when I really started delving into pre-code, for instance. It was at about that time that I decided to take a look at a movie I’d seen listed on almost every greatest movie list I’ve ever seen. That movie is Fritz Lang‘s M (1931) and it changed me irrevocably.

So here we are in 1931, the early days of sound in the movies. For the most part Hollywood is serving fluff, either all-singing musicals and or all-talking theatrical adaptations that the industry thought best suited the new innovation. And then there’s M, Fritz Lang’s first sound picture, an unusual piece of storytelling that is at once disturbing and fascinating on several levels. (Before you continue note that you will be spoiled if you read on.)

As Fritz Lang tells it here is the story in M –

A German city is in a state of terror, an uproar where all factions of society are forced to action. The cause of the terror is a serial killer of children, an implied pedophile named Hans Beckert. Beckert (played by Peter Lorre) is a pathetic, pudgy, otherwise nondescript young man who whistles Edvard Grieg’s “Hall of the Mountain King” from “Peer Gynt Suite No. 1” when he gets near children as his horrific compulsion takes over. To say that one is uncomfortable watching M is an understatement. I’ve only been able to watch this perhaps three times because it takes its emotional toll. Lang manages to render the viewer incapable of looking away while also wanting to turn away in horror.

M begins with a group of children singing a German version of what I gather is “eeny, meeny, miny, moe” except that in a little girl’s voice the loser of the game as the lyrics dictate will be made mincemeat at the hands of a monster. I played what I assume most would consider a strange version of “eeny, meeny, miny, moe” myself as a child. In Spanish. I don’t remember the exact rhyme, but the loser in my case, the final “moe” had to step into a pitch black vestibule under the stairs of one of the buildings on our street and try to summon up a ghost or spirit. I’m happy to say no ghost ever heeded my call, but the five minutes alloted to each potential encounter felt like a year and a half. It was awful, but in retrospect me and my friends had nothing to worry about, our strange game was nothing more than a way to beat boredom. In contrast the children in M sing about the worst kind of horror imaginable. A real horror and Fritz Lang sets the stage immediately. One mother admonishes the children for singing such an awful song, but another reminds her that as long as they’re singing everyone knows the children are still alive. That second mother’s little girl doesn’t make it home from school that day. Or any other day.

That’s really all that needs to be said about the actions of Hans Beckert. Knowing what types of crimes sets the story of M in motion is enough to make one want to recoil, but it’s the way Fritz Lang tells this story – both visually and audibly – that is memorable. Amidst the gruesome Beckert crimes Lang layers social commentary presented as the frenzy to catch the child murderer is set in motion. The police have pulled all of its resources to raid all of the known establishments of the criminal underworld in hopes that the notorious killer is hiding among the dregs of society. The raids severely impede the activities of all factions of criminals – from beggars to thieves – people whose livelihoods depend on daily criminal activity and who are none to happy to be listed alongside a child murderer. In response to the increased police activity the chiefs of the underworld who I always equate to the heads of the five families as seen in Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), set up a meeting to discuss the raids, a meeting that ends with an agreement to galvanize the underworld in order to catch the killer themselves.

At the same time that the leaders of the crime syndicates are discussing how to catch the murderer the authorities are having the same conversation. Fritz Lang presents the parallels in a superb montage intercutting between the gatherings where the groups assign blame and come up with a plan, each meticulously laid out. With impressive organization the criminals set up a system where beggars are assigned an area on a grid, collectively covering the entire city so that they can follow any man who looks suspicious. At the same time the police gather information from asylums and psychiatrists where they think the murderer may have had a file at some point. With everyone moving toward the same goal both the law and the underworld narrow in on Hans Beckert at the same time.

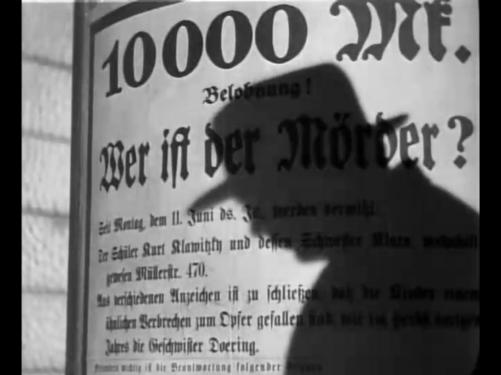

Hans Beckert whistling “Hall of the Mountain King” signaling his frame of mind passes by a blind man selling balloons. The blind man recognizes the tune and realizes the last time he’d heard it was a day a child was murdered. The blind man calls another one of the beggars who sees Beckert talking to a little girl. The chase begins with Beckert’s coat marked with an “M” for “Mörder,” the German word meaning Murderer. With the “M” written on the palm of his hand with chalk one of the beggars manages to mark Beckert so that he can be tracked by other beggars in a cat-and-mouse relay until the murderer is surrounded.

The conclusion of M forces us to consider justice in arguments presented by experts in the law – the criminals. Hans Beckert is brought before a tribunal where justice is to be rendered, a kangaroo court in which the heads of the criminal divisions preside and where all other factions of the underworld stand in as the jury. In truth justice has been rendered before Hans Beckert was carried by force into the makeshift courtroom, a literal underground space laid barren by war and abandoned by society – not unlike justice in the eyes of this court.

The verdict is Beckert will never leave that hall of justice because if left up to the authorities he would be labeled insane, treated and probably released as the law so often fails. It’s difficult to argue with these criminals. But then Peter Lorre as Hans Beckert is allowed a monologue in what turns out to be one of the most affecting scenes in movie history by my estimation.

Beckert stands horrified in the kangaroo court denying any wrongdoing, an animated wild man standing up against steadfast accusers. Except he is not now overcome by the horrific impulse, inebriated by evil as we saw him in an earlier scene. Here Beckert is a man with a psychosis – an important distinction.

Defeated by his accusers Beckert falls to his knees and renders his own judgment on those who stare, describing with guttural accuracy the struggle within him. It’s an astounding portrayal that we watch and listen to with horror because as Lang intended we come to feel empathy toward this monster, as wretched a creature as I’ve ever seen. We are infected with grotesqueness – the psychosis up against monotony in a litany of words at the end of which we hate the impulses and acts, but not the man.

Peter Lorre’s depiction of Hans Beckert is brilliant. The not yet widely known former Berlin stage actor delivers a highly stylized performance he’d never be able to escape from. Lorre who was Jewish would flee Germany not long after the release of M and as we know he would have a long career in Hollywood, but unfortunately mostly as a character actor portraying monsters or schemers in one way or another for the remainder of his career. The English version of M, in which Lorre speaks the final monologue in the film himself was his first starring role in English. That version, which incorporates dubbing and silent scenes from the original was directed by Eric Hakim.

Fritz Lang considered M to be his favorite of his own films because of the social criticism in the film. In 1937, he told a reporter that he made the film which screenplay he co-wrote with his wife, Thea von Harbou “to warn mothers about neglecting children,” which sort of reminds me of Howard Hawks’ Scarface (1932) and how a caveat to audiences was added to appease the censors. That caveat in no uncertain terms told viewers that such crimes existed because they put up with it. Lang delves too deep inside German society in that time for me to accept M as simply a warning to mothers, even if the warning is served as the last line in the movie.

Although I’m now all too familiar with M it’s still difficult for me to believe it was made in 1931. It is not one of the best movies of that decade, but one of the best movies made in any decade. Aside from Lorre’s memorable performance M serves plenty on the artistic side that I imagine was innovative for 1931. Lang’s choices with sound are one part of that. M has several silent sequences that prove thrilling and suspenseful in themselves, but then you are often unnerved by sudden sounds just as Beckert is during the chase. Given this is an early sound picture the fact that the sounds are used sparingly, if you will, yet play such a key part of the story is extraordinary. For instance, there is no way to get over the haunting echoes of a mother calling out her child’s name, a child we know can no longer hear her. There is no way to not get chills when we hear the whistle that signifies a child murderer lurks. And the genius to have the murderer caught by a blind man by way of sound is ever fascinating.

Fritz Lang also makes memorable statements in M visually by the use of shadows – imposing shadows that linger. Also used are terrific long shots from high above the action that take the viewer outside the story in a way, reminders we are watching a theatrical endeavor, dispassionate displays at emotional times. Although Lang doesn’t show any acts of violence or deaths of children on-screen, he does suggest the violence by (as he said) forcing “each individual member of the audience to create the gruesome details of the murder according to his personal imagination.” It really takes little imagination for anyone who watches this movie to go “there” with images of a balloon held by a little girl just a moment before now loose or the ball a child was bouncing now rolling aimlessly. Every single one is an overwhelming image.

That is the horror of M, one of the greatest films ever made.

♦

The complete cast and crew list of M is available here.

I’ve wanted to comment on M since the first time I saw it, but have never found the courage to do so until now. It’s not a simple matter for me to say I love a film that deals with the worst possible subject one can conceive, but I do. And there you have it – so that’s why I chose this Fritz Lang masterpiece as my entry to the The Fabulous Films of the 1930s Blogathon hosted by the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA). The Fabulous Films of the 30s event runs from April 27th to May 1st. Please visit the CMBA every day this week to get the lowdown on many of the greatest movies of one of classic Hollywood’s most glamorous decades!

ALSO…

If you want to jump the gun on reading some of the entries, the CMBA is proud to present The Fabulous Films of the 30s in eBook form, containing 19 of the essays to be presented in the blogathon. So that you are aware – I didn’t submit this entry to the eBook publication, but it shouldn’t be missed!! The eBook I mean. It’s available for free at Smashwords and for $0.99 at Amazon! All proceeds will be donated to film preservation.

Wonderful review. I have never seen this film but now feel I should.

Thank you, Vienna. Difficult to watch, but as essential a film as there is.

I appreciated your highlighting Lang’s use of sound in a movie that is almost too overwhelming. The story, Lorre’s performance, and the images are indelible. I think one should realize that before watching “M” for the first time. You can never forget it.

I’m putting this one away for years before I watch it again. It was actually a bit of a struggle to step out of personal feelings and comment on the story and elements depicted.

Reblogged this on the last drive in and commented:

Aurora from Once Upon a Screen takes on Fritz Lang’s eerie masterpiece M…

Nice post, Aurora. I love Fritz and all his movies especially M. What I love from this era is the power of imagination put into the audience’s head instead of today’s ultra-realism. I think something is lost now.

Have to agree! The simple, yet powerful images leave a much longer lasting impression than blood and gore.

This film haunts me too, particularly the opening sequence, and I agree that it’s daunting to review it! You did such a beautiful job. I feel everyone should see it, not only due to its artistry, but because its sympathies force us to look at ourselves as well as the murderer–which so rarely happens in film. I had never thought of the brilliance of the choice of the blind man as his (eventual) enemy. Such a great point. Leah

Wonderful post, Aurora. “M” is such a powerful and important film – you couldn’t have chosen a better film to write about. It is almost like a ballet, isn’t it? And once you see it, you never forget it. I liked your intro about growing up loving films of the 40s. For me it was the 30s and then I started working backwards to the 20s – I guess that’s how it works!

Wonderful post on one of the great films of the 30s. Lorre is a truly great actor, but sometimes gets lost because of all the horror films he did later in his career.

I read something about sound design in the early 30s that it wasn’t so much Hollywood had to learn how to use sound, it was that they had to learn when to shut up. I think M is one of those perfect early cases where Lang nailed it. I haven’t seen this one in quite a while, Aurora, but thanks for bringing back several vivid memories. 🙂

Aurora, M is a brilliant film and your review is superb. I love your opening paragraph. No one can play slime like Peter Lorre! I love the way both the police and the underworld, for different reasons, want Lorre’s character off the streets. Lang sets this all up with style. A powerful and excellent piece of filmmaking.

Aurora, I admit I skipped bits of your review because I haven’t yet seen this film. (I know, I know.) You’ve now made this an urgent item on my Must Watch List.

I was struck by how objective your review is, considering the subject matter of the movie. Nicely done.

You summed up my assessment of M perfectly when you wrote: “It is not one of the best movies of that decade, but one of the best movies made in any decade.” Fritz Lang was an incredible director and made many fascinating films. However, M remains his masterpiece, both thematically and technically. The scene with the ball is nothing short of brilliant and once again proves that what one imagines is always horrifying than what one sees.

Great review and really love this film. 🙂

Great review of a complicated, brilliant movie! I particularly loved your description of the criminals’ court: “We are infected with grotesqueness – the psychosis up against monotony in a litany of words at the end of which we hate the impulses and acts, but not the man.” Wonderful!

Thanks for the review! M is my favorite Lang film and I couldn’t agree with you more. I also felt that Lang’s explanation of the film was a bit of a cop-out. Could it be that this master of creepiness managed to disturb himself?

A beautiful essay on this essential movie. Lorre was one of the greatest film actors of all. I really think he could do anything, but as you say, he got few chances. Three Strangers lets him be the good guy, which is really enjoyable. And while a lot of people disagree with me I adore him in The Mask of Dimitrios. His monologue after he’s been convicted in M was indelible, nobody who saw it could forget it. I wonder why some actors get stuck in typecasting hell after a career-making performance as Lorre did, while others (Bogart) carry a strong identification with their biggest success but still manage to play all kinds of characters?