Since its beginning, cinema has been inspired by many other art forms – but none has had the impact on the telling of stories on the big screen as literature, the written word, more specifically, books and novels. As source material, novels have dealt motion pictures huge varieties of topics and stories from which to choose. Certainly not all films that have been adapted from books have been good. Many have been downright terrible. It is actually a rare thing for a book-to-film adaptation to have an end product that is as good as the original work, and rarer still for it to be better than its source. However, one cannot ignore the list of film classics that have resulted from the transition. Among these are Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolfe? True Grit, The Three Musketeers, The Silence of the Lambs, A Place in the Sun, One Flew Over the Cookoo’s Nest, The Maltese Falcon, The Grapes of Wrath, Dracula, All the President’s Men, To Kill a Mockingbird, and The Godfather. Though the quality of the source material used for these films varies, many would agree that the film adaptations mentioned here are among the greatest motion pictures ever made. The last one listed here, The Godfather (and its sequels) is the one to be discussed at length in this entry, Spoilers included.

Both Mario Puzo’s novel about the life of the Corleone family and the subsequent films directed by Francis Ford Coppola have been the subject of much discussion by Hollywood “experts” and by the millions of fans who never quite get enough of them. The novel’s greatest achievement is perhaps the films that it spawned – films that have inspired direction, iconic performances, memorable music and dialogue that have become a part of our vernacular. In short, films that are unforgettable.

The story of The Godfather as depicted both in the Mario Puzo novel and in the first two installments of the films of the same name is multi-faceted. On the one hand is the world of organized crime, the Mafia or Cosa Nostra. This is a world where ties are strong, loyalties are somewhat flexible and tempers are short. It’s a world full of revenge, violence and distrust, and a world where the weak cannot survive. Mistakes in this world are lethal and usually very expensive and friendships are easily bought. On the other The Godfather tells a story about family – the blood family one is born into and the one where you have to prove yourself to belong. Varying degrees of power and control and the price paid to achieve success surrounds both of these. This is the world we are introduced to, the world of Vito Corleone. “I believe in America…”

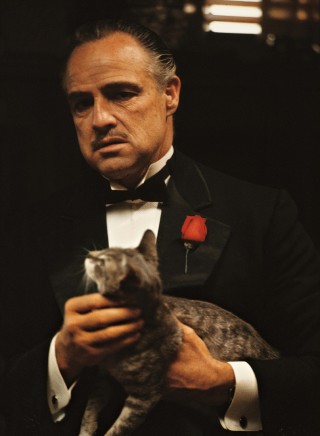

Don Vito Corleone, or simply Godfather as his “friends” and loyalists call him is a man with no regrets, for he has succeeded in providing for his family in the only way he knew how. Vito Corleone is at the top, a man who has proven his strength, who has unquestionable power and yet never forgets a friend. Though he is to be feared, it is not by brute force alone that he has become the most powerful Don in the world of organized crime. As Mario Puzo introduces us to this unique man, on the day of his daughter’s wedding when people come to him for favors, at the very beginning of his novel we learn that “Don Corleone received everyone – rich and poor, powerful and humble – with an equal show of love.” In turn and rightly so, Don Corleone is loved by his family and friends and respected by his enemies. He has struggled to make it to where he is and deserves all the accolades bestowed upon him.

There are many things that occur between the finding of a book source to base a film on and the release of that film. These things often result in a “watering down” of the original story so that the final film product barely resembles the original source material. The exceptions to this are few and far between, relative to how many films have been completed from previously published books. A few of the exceptions are mentioned above. However, even these exceptions can rarely be exactly as the original source. For instance, depending on when a film was made there may be cinematic conventions to consider (like the old production code), run-time limitations because movie audiences have limited attention spans, budget considerations, etc. In short, the reasons for varying from the book may be numerous. The Godfather is one of the ones that remain fairly true to the original source – or as close to it as a 175-minute film can. Though it is the opinion of this fan that the film versions of The Godfather do, in fact, better on Puzo’s novel, Puzo’s collaboration with Francis Ford Coppola on the screenplays has to be credited for the films remaining so true to the characters and story he originally put on paper. However, the subtleties not included in the films, the differences that for some reason could not make the transition are in themselves worthy of discussion.

The differences between Mario Puzo’s novel and the film versions have to do mostly with character history where several of the peripheral characters in the films are given more attention in the novel. In some cases extensive backgrounds are omitted from the films probably due to time constraints. The first character that comes to mind is Captain McCluskey. In the film version of The Godfather, McCluskey is simply a corrupt police captain, the death of whom, by Michael’s hand turns the tide of the story and forces Michael to fulfill his destiny. In the novel we learn of McCluskey’s upbringing and how it lead to his becoming a corrupt cop. A road to corruption that was paved by his father and grandfather who’d shown him that corruption was the way to make it out in the real world. It shows why the monetary price of law outweighed the need for order. To him order always came with the greasing of his palm. None of these details are included in The Godfather film.

Another major difference between the novel and the films comes by way of the attention paid to the character of Johnny Fontaine in the novel. Though Fontaine plays a small role in Part I, the part he plays in Puzo’s book is more substantial. Here we get an in-depth look into his relationships with young starlets, with his wives, with his daughters and details of the trials and tribulations he lives through related to his career. In both versions, however, one scene stands out as key and in the film becomes as memorable a scene as ever appears on the big screen. Though Fontaine is not in the scene, it is because he is the Don’s godson and has come to ask a favor of his godfather that the scene plays out. This scene is the one where movie mogul, Jack Woltz, discovers the head of his beloved Khartoum in his bed. In the film the scene opens with a glorious, peaceful morning in Hollywood. The camera pans across the mogul’s majestic estate while birds chirp happily in the background. Slowly, the camera ascends toward a small window and that music – possibly the greatest of theme songs – begins to play ever so softly as the camera continues to move upward. Through the window we go and upon a slumbering Woltz we come. In an overly ornate bed he lays on satin sheets, the music swells and the camera now follows him as he discovers blood. He uncovers the head of the horse and the music dies leaving us in the midst of a gruesome sight and blood-curdling screams. It is unforgettable.

In the novel Mario Puzo also goes into much detail about the awesome Luca Brasi. In the film Brasi’s past is briefly mentioned during Michael’s telling to Kay of the now-famous releasing of Johnny’s singing contract and the Don having made “an offer he couldn’t refuse” to a bandleader, while accompanied by Brasi. “He’s a very scary guy” is really all we learn of the massive man. But the extent to which Puzo tells of Luca Brasi’s crimes is lost in the film. In the novel Brasi is a one-man cosa nostra unto himself. He alone saved the Corleone family’s reputation when the Don had been injured in the 1930’s. Also mentioned in the novel is that Luca Brasi had gotten a young girl pregnant and arranges for the baby’s disposal and kills the girl himself. This man is a killing machine and the reason why Puzo gives him such importance in the novel is that Brasi is the only man the Don himself would have feared if he were to fear any man. Luckily, in both cases Luca is blindly devoted to his Don but the impact of this strong character is never felt in the film where clearly, there is no man Don Vito Corleone would come close to fearing.

Lucy Mancini, Connie’s bridesmaid, who we see in the film as the “young girl Sonny is making comedy with” has no bigger purpose than that in Part I (she does appear later in Part III in a small part as Vincent’s mother). In the novel, however, much in the same way we learn about Fontaine’s life, we learn about Lucy’s. With the help of the Corleones she moves out West after Sonny’s death. She continues her life in Vegas and becomes involved in one of the Casinos. She meets and marries a doctor who helps her overcome a sexual “defect” and they live happily ever after. Also in the novel Lucy never has children, which of course would leave the Corleones without an heir to the throne in Part III.

There are other peripheral characters with mere mentions in the films that are fully rounded and detailed in the novel. Rocco Lampone and Al Neri, who become major players in the new generation that become strongmen when Michael becomes head of the family, are rarely even referred to by name in the films. Each has a story to tell and comes with baggage. Of all the characters in both versions, however, the one that makes the biggest change from one medium to the other is Kay Adams. In the novel we learn about and meet her family and what they feel about Michael – mostly that they are vigilant for their daughter but trust her to make her own decisions. Though in the film it is obvious that Kay is not the “typical” mafia wife from the beginning, the fact that she grows increasingly distrustful of him, his lifestyle and work is a major source of drama in the first two installments of The Godfather films. In the novel, however, Kay is blindly in love, continues a connection to the family through Michael’s mother during the time he is in hiding in Sicily and in the end becomes the “typical” woman who would marry such a man. She not only learns to accept him and what he does, but she converts to Catholicism so that she can attend church and pray for his soul – just as his mother does for his father. This is a major discrepancy between the novel and the films because Kay’s growing disdain of Michael in the films is vital to his eventual alienation.

Merriam-Webster defines a masterpiece as “a supreme intellectual or artistic achievement” and therein lies the biggest difference between The Godfather, the novel and the first two films in the trilogy. Mario Puzo’s novel was a great commercial and critical success when first published in 1969. For the most part it was hailed as “absorbing drama” and according to Pete Arthelm of Newsweek (3/10/69) it was “a big, turbulent, highly entertaining novel.” Dick Schapp says, in his NYT Book Review (4/27/69), “Puzo has written a solid story that you can read without discomfort at one long sitting.” Few people, including this reader, would disagree with those opinions. Nor would they disagree with the fact that Puzo must be credited with supplying such rich material from which these masterful films could draw. Since Mario Puzo co-wrote the screenplays with Francis Ford Coppola his hand is all over the films but he has to be credited most with the fact that audiences so connect to the members of an organized crime family, something so vital to the success of the films. People would not watch these films over and over and they would not have become so ingrained in American culture if not for the characters created by Puzo. However, even after saying all that, one has to admit a masterpiece the novel is not. It is a great story and this reader can attest to the fact that it is never boring. But it wouldn’t be far fetched to compare it to any number of other novels written by other popular fiction writers. Oh, but the two first films it spawned are another matter altogether.

The Godfather, released in 1972 seemed to reap the rewards of having been produced at the perfect time, a special place in history, both for American society and for film. The 1960’s saw the final demise of the production code in Hollywood and world events that awakened audiences to tragedies of unspeakable horror – assassinations and wars now depicted on screens in real time. Due to these and other factors, a new kind of grittier, more realistic film was being made. Filmmakers were more prone to make the films they wanted, even if they depicted criminals as heroes (something the Code would have rejected). Also, with what was happening in the world – the Vietnam War, Watergate and the like – audiences could no longer be fooled; they too wanted realism in entertainment. Francis Ford Coppola, one of a few of a new generation of directors, along with Martin Scorsese and others, also wanted to show his vision as it was in real life. And then destiny showed its hand, for a better coupling of material (Puzo’s novel) and vision (Coppola) could not have been made. The impact of Coppola’s filming of Puzo’s story resulted in the making of cinematic history. The Godfather became, up to that point, the highest grossing film of all time (it was toppled by Jaws three years later) and Coppola brought the gangster film, one of the oldest and most popular genres in Hollywood, to new heights. Staying true to Merriam-Webster’s definition, The Godfather is “a supreme artistic achievement.”

It would be a serious undertaking to note all that makes The Godfather a great film, a masterpiece, because so much of it is unforgettable. It is simply a staggering film with so many great moments, performances and lines that one cannot mention them all. So, of all the examples to choose from the following stand out as a mere sampling. The acting – it is phenomenal – each actor perfectly personifies the character he/she is playing. Marlon Brando plays the title character with as much style and grace as he does his many other performances. The man does not miss a mark or nuance. Playing a man much older than himself, a man in the twilight of his life, he commands the respect and honor naturally given to all leaders of men. However, despite Brando’s great performance, one he won an Academy Award for, it is not the best in the film. That honor has to go to Al Pacino whose portrayal of Michael Corleone, the Don’s youngest, and smartest son still stands as the best in his career. Pacino’s gradual transition from a young, fresh-faced war hero to the tortured head of the most powerful crime family is nothing short of amazing. It’s all done brilliantly subtle, or subtly brilliant – whichever way one looks at it, it works. For instance, how his shoulders slump and his posture change throughout the film as the weight of the world falls upon him, is astounding. Although it is clearly more visible in Part II, we can already tell that the Michael Corleone who is morphing into the next Don in front of our eyes is a different man than he is in Puzo’s novel. Michael here is much more introverted, much more tortured by his decisions, which somehow make him more menacing.

Pacino’s performance in this film alone is enough to make it memorable, but there is much more. James Caan’s portrayal of Vito’s oldest son, Sonny, with the live wire temper is also great. It is in this role – one that differs from the novel in that Sonny seems less capable in the film due to the fact that the film doesn’t make mention of his past accomplishments and experiences during a previous war between the families – that we see the brilliance of characterization come alive. Sonny is an extremely violent man, prone to losing his temper at the drop of a hat. He’s impulsive, reckless, shoots off his mouth all the time and yet when we see the nasty way he is murdered we mourn for him. How is it that we come to care for a man such as that?

John Cazale plays Vito’s second son. The runt in the clan, Fredo. A weak man who sticks out like a wounded fish amongst the sharks in the few scenes he’s in. As the only male character in the family with absolutely no power and no strength of character he becomes a quiet force for attention.

The last major performance I’ll mention here is Robert Duvall’s as Tom Hagen. The way Duvall plays the smart, needy, vulnerable man who does much of the Don’s dirty work comes across beautifully. His need to belong is ever-present.

During the casting process filmmakers can do a great service to a film by matching actors to the characters of an original book source so that at least that part of the visual realization is done prior to the beginning of filming. And due to much of what was mentioned above the casting in the first two installments of The Godfather on film was inspired. However, it is not the only aspect of Part I that matters in a historical sense, nor is it even the best. It is the other choices made by Francis Ford Coppola to bring this film to life that make it his crowning achievement as a director (in my humble opinion). In this case he is a director directing the film he was born to direct. That crowning achievement is the look and feel of this film.

“The Godfather is a feast of a movie – you come out of it craving lasagna and meat sauce” one critic said of the film and truer words were never spoken. Coppola seems to know the intricacies of these people, the times and the places like the back of his hand. This is why much of this film feels like a home movie, in a sense. A Cinema Verite of the crime world and the Corleone family. The mood of the film is constant, a definite power and as palpable as any one of the characters. The film has perfect setting, period costuming, sound; music one never tires of (including the theme music, which is often manipulated for mood – from romance to warning of impending doom) and on and on. But it is the brilliant cinematography of Gordon Willis that is groundbreaking and is as much a part of The Godfather legacy as any other aspect of the film. (It is a good time to note here that astonishingly, Willis received only one Academy Award nomination for his groundbreaking cinematography on all three films in the trilogy and that was for The Godfather, Part III). This film would simply be a completely different film if it didn’t have the orange hue lighting, the lights and shadows and the feel of a film shot during the golden age of Hollywood, despite its color. The lighting remains intimate throughout – a single lamp in the hospital room, eyes kept in shadows to enhance the menace of a person, the warm lighting that makes a home feel like a home despite the goings on, etc. – we are privy to the most intimate moments of these people. This is where the film betters Puzo’s novel. Puzo introduces us to the story, settings and characters but Coppola brings us into their world. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words and the pictures within this picture – all memorable, all outstanding – are too numerous to count.

The Godfather, Part II, released in 1974, continues the story of the Corleone family as originally written by Mario Puzo, for about one-half of the film. Michael, now the most feared man in organized crime becomes more and more alienated from everyone who surrounds him. By the time this part of the story begins Michael needs not prove to anyone he can lead his family and/or defeat his foes. Now the task to be conquered is within him. The power he’s attained and killed for wears on him. He no longer trusts even those closest to him and soon loses the sense of where enemies end and family starts. Incidentally, this is a line that never blurred for his father.

Al Pacino continues his bravura performance as Michael. His growing bitterness and loneliness grow from deep within and engulf his every step. The coldness of this man is set deep in his eyes and make this character one of the most menacing ever to be portrayed on film. It is difficult to think of another actor in another role that can – simply with a flick of his eyes – say so much, or be so scary. When he’s hugging Fredo at his mother’s wake, all it takes is a flick of his eyes toward Neri and we know the doom that is to come. When Kay is at the door after visiting her children behind Michael’s back and he happens to walk in on her – the look in his eyes as he closes the door in her face chills one down to the bone. No other man but Pacino could have played Michael Corleone in this manner.

Throughout Puzo’s novel there is mention of destiny. The Don believes heavily in destiny, and there is no doubt in him, or in us, that he was where he was supposed to be at all times. His life and his work were the destiny that he brought to fruition for himself. This is pertinent because although destiny is not necessarily a spoken theme in the films one cannot ignore that it is the reason Michael ends up as Don instead of one of his brothers, and it is also where he differs most from his father. Michael’s destiny to become the head of the family trickled down to him, was handed to him. Yes, it is his destiny but to a large extent he felt obliged to do what he had to do. While it came naturally to him he would always be at war with himself and always present is the “why me?” aspect to this man. The life he leads is not the one he would have chosen. This Michael is in contrast to Vito but also to the character of Michael in the novel. In Puzo’s book Michael is surer of his role as Don and in the world that surrounds him.

The Godfather, Part II is another brilliant Francis Ford Coppola’s direction. For this film he went on to win the Academy Award for Best Director. Here we see not only the development of all the familiar characters in the present time (the late 1950’s), but also the story of how the Don came to be through flashbacks of the Don, Genco, young Clemenza and Tessio in the old neighborhood as they began their business association in the Genco Olive Oil business and beyond. The flashbacks are straight from the Puzo novel as he covers Vito’s rise to power as well as Michael’s. But there is much in the plot of The Godfather, Part II that is new to the Corleone story and not covered in the novel. The first thing is the major plotline having to do with Hyman Roth, the Jewish boss who is Michael’s main foe in this film. Another is the senate investigation that plagues Michael and threatens his empire. Fredo’s betrayal, which leads to the descent of Michael’s soul into a place from which there is no return – and all that results from that are all also native to the film. And finally there is the increasing unhappiness of Kay in her marriage and her subsequent breakup with Michael. As mentioned above, this is something the Kay in the novel would never have even considered.

The Godfather, Part II is a much more complex film than the first. The style of storytelling is very similar to that of the novel in that Mario Puzo also uses flashbacks to tell the story of Vito’s rise to power contrasting it to Michael’s. Again, the contrast between the two is much more severe in the film because Michael’s growing bitterness is not present at all in his father and the going back and forth between the two parallel stories emphasizes their differences beautifully and more profoundly. Vito is a calm, confident and fair man from the very beginning. He is never conflicted and always seems sure of what his next step should be. This man is definitely doing what he was born to do. To his son, however, fate has dealt a mighty blow, a blow from which any number of people may not recover.

As in Part I, Part II features the same brilliance in setting, cinematography, period costuming and music – in short, all the things that made Part I a special film are again present here so that there is no need to go into detail about these things again. Suffice it to say that the mood is always perfectly established to whatever time and place the story takes us. The acting is also astounding in this film – and it is clearly evident that these actors and directors are in their prime. Much of what comes through in this film will never be bettered by many of the players (with the glaring exception of DeNiro’s performance in Raging Bull). Details of Pacino’s performance are mentioned above but some of the other players, a larger supporting cast than in the first film, cannot be ignored. Michael Gazzo as Frank Pentangeli is great, Lee Strasberg as Hyman Roth is very convincing as Michael’s ill foe, Robert DeNiro as the young Vito Corleone is magnificent and again, John Cazale as Fredo is a favorite and deserves another mention here – such a brilliant actor. Cazale brings the heart-breaking, often pathetic Fredo to new depths and one cannot help but feel for this man and the fact that fate may have actually mistakenly brought him into the wrong world and the wrong family. His “I’m smart…I was passed over” scene is wonderful. It’s terrible. It’s heart wrenching.

Many people consider The Godfather, Part II the superior of the first film, and in many aspects it may well be. It is complex and long and yet never boring and never stumbles on its way to telling a very compelling story. There is no way around the fact that this is an extraordinary film and an absolutely incredible accomplishment. However, there is a certain affection that this fan holds for Part I that is not replicated here. Though difficult to put into words one has to attribute it to the family dynamics – that simplicity and comfort of home that is not present in this second film, with one small, joyous exception. At the end of Part II, as Michael sits outside contemplating about how far he has gone, how he has reached a place from which there is no return, he thinks of the old days and in a flashback we are taken to a day when the family celebrated the Don’s birthday, a surprise party. All the young Corleones are around the table and things are as they should be. Sonny is animated and hotheaded. We hear one of his small daughters in the background say “mommy, daddy is fighting again.” Fredo is innocent and naïve, Connie and Carlo have just met, Tom is the spokesman, trying to keep the peace and Michael is the outsider, having just joined the Marines because Pearl Harbor has just been bombed. We hear Sonny say “What do you think, the nerve of them Japs, them slanty-eyed bastards? Dropping bombs on our own backyard. On Pop’s birthday, you know?” The world revolved around them then and who wouldn’t have wanted to be a fly on that wall? It is in that time and place that we seem to be at home and it is with much regret that we let go and admit those times are gone forever.

The Godfather, Part III continues the Corleone family story as of 1979. Michael, still the head of the family, has tried since last we saw him to bring legitimacy to the family. Since he is being bestowed an honor by the Catholic Church at the film’s onset we think for a moment he may have succeeded, but we know what he’s done to get to where he is. And we know what weighs on his soul.

The screenplay for this film, like the other two, was co-written by Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo. The story here falls well outside the one covered in Puzo’s novel. In the sense that these two men know these people better than anyone else there is closure to these people’s story and the movie feels like an homage, in many instances, to the fact that we need to know what happens to them. Aside from that, there was no need to make this film. Although Part III is good enough to stand on its own merits a lot is lost if one is not familiar with the first two films, which somehow manage to fill in the gaps left by this one. In many instances, the dialogue, which seems forcibly written to sound like that of the other two, seems awkward and often stumbles along – a fact that is that much more obvious if one happens to watch this film in close succession to the other two.

The plot involves the Catholic Church as one of the greatest evils in the world and how Michael’s efforts to bring the family into the right side of law and order fail. Michael is tired, old and trying to make amends for his sins but no matter how hard he tries “they keep pulling him back in” – his fact is compounded by Vincent Mancini, Sony’s illegitimate son who’s eager to lead the family and avenge any and all enemies. The fact that Vincent eventually becomes heir to the Corleone throne is bothersome, at best. This does not feel like destiny and perhaps it is Michael’s loss of will, his exhaustion that lead him to appoint Vincent Don – of course Michael’s only son has no interest in family affairs. But still. Vincent just has not “made his bones” and on some level it is a slap in the face to the memory of Vito Corleone, a man we so loved and respected, that this should happen. The rite of passage seems unfulfilled, at least to this viewer

As far as The Godfather, Part III being a film worth watching, it is. There is much in it that works, despite the overwhelming popular outrage that it is terrible. All that is right about this film is all that is familiar. The mood here is not as consistently rich as it is in the first two films but we are, to a great extent, back to the familiarly lit rooms inhabited by this family. Rooms filled with shadows and memories that we enter with great ease. And why not? We’ve been here before. Back again is the theme of religion versus evil, a theme so prevalent in the first two films – scenes that intercut a religious theme with gruesome violence. The importance of familiarity is clearly not lost on the filmmakers in this case, as what they have to bank on is a return of all those Corleone aficionados. During the opening sequence, when we hear that familiar theme music playing, when the camera pans around the grounds we’ve come to know – the gazebo/bandstand where we attended Anthony’s communion, the fateful river where The Hail Mary was once said out loud, the home, now abandoned – it is indeed a welcomed sight. And in keeping with the feelings of familiarity is Kay Adams, back again as the only person who would/could ever tell Michael the truth to his face. Kay appears still angry at the fact he could have been a different man, but is now again a part of his life. It should be noted also that the scenes between these two characters are the best in the film. They alone tie much of this film to the others as Kay constantly reminds Michael, and us, that in reality he hasn’t changed all that much, he’s still a gangster, a common Mafia hood, despite all the titles and honors bestowed upon him.

As far as the acting in The Godfather, Part III, it is adequate in comparison to the other two Godfatherfilms. That’s not to say there is no bad acting – there is. But no need to go into details about that. Still, many of the key players are still worth watching. Al Pacino loses some of the subtlety that made his performance in the others great. It must be noted that now Michael feels a need for redemption and confesses several times in the film – to the Cardinal and later to Don Tommasino as the old man lies in his casket. This is understandable as the need to absolve himself of sin, clear his conscience, becomes ever present as the end of his life nears. However, in comparison to the Michael of old, this one seems verbose and Michael the confessor is often unrecognizable. (That is, to a viewer who has the Michael of old so ingrained in her mind and heart). Al Pacino does have his great moments in this film, however, as in the scene on the Opera house steps when his daughter Mary is shot. If the audience is not moved by that silent scream of a man in pure agony then it is unfeeling.

Another significant change is seen in Connie Corleone. Finally, at the end of the entire Corleone saga, do we see a woman making some “bones” of her own. Connie, now Michael’s companion and caregiver is in complete support of her brother. She pushes Vincent to be ruthless and act like what she perceives a Don to be, often stirring him to act out vengeance against Michael’s enemies. But Connie plays a larger role in the “family’s” dynamic than any other woman has ever done – for her brother she commits murder herself by killing her own godfather by poison. Connie, the “spoiled guinea brat” that only caused problems for her brothers as a younger woman is now a force to be reckoned with and would have made her father proud (if her father had believed women had a place in “business,” which he didn’t). Without other siblings, Michael, the Don, is now lucky to have her by his side. (This is a good time to mention how much the absence of Robert Duval as Tom Hagen is felt in this film. Had he been by Michael’s side perhaps things could have been different. No doubt the film would have been much improved with Duvall in it.)

Finally – the manner in which Michael Corleone leaves this world, closure to his story. Here is a man who has seen and caused much heartache and violence. He has experienced the death of those closest to him, in most instances long before nature would have dictated, including that of his beloved daughter during a botched assassination attempt against him. There is something evil, though ironic, that he should die alone and simply by slumping over while eating an orange in old age. Destiny never offered to take him out of his misery, though there were attempts against him. Instead, it dealt him a long life during which he’d be forced to ponder and suffer in silence about the sins he committed on this Earth. This seems abnormally cruel and seeing this man, whom we’ve come to love despite his sins, slump over never ceases to stir.

The trilogy is now over. Whether one prefers the novel or the films is a personal matter. To me they are all worth your time. Over and over again. Regardless of the form, the fact remains that the story of the Corleones is a powerful and affecting one. It is timeless and it is relatable. In a real sense it is a story about every family everywhere –their feelings, loves, joys, sorrows. We all become participants in these people’s lives, and their crimes. Willingly.

This is a case where the review lives up to the subject that is being discussed.

I agree with most everything you said. I am not as big a fan of the third movie and that might be because so many years elapsed between the second and the third. I think it lost some momentum by that lengthy delay.

John Cazale is the linchpin for the first two movies. His performance really pulls everyone else in his scenes to a rarified height.

Thanks for reading this and I’m glad you enjoyed it. I think most feel as you do about Part III. It certainly is nowhere near the first two in quality but I don’t hate it. Unless I watch it immediately after its predecessor. Then it’s a jolt.

I agree about Cazale.

Aurora

Outstanding post, The first two are amazing films.

What’s up, I log on to your blogs daily. Your humoristic style is

awesome, keep it up!

This website definitely has all the information and facts I needed about this subject and

didn’t know who to ask.