Crime and criminals have been the focus of motion pictures since the birth of the medium. However, it wasn’t until the sound era (the 1930s) that gangster films truly became an entertaining, popular way to attract audiences to theaters for a “full” experience, one might say. The reason for this is rather obvious – sound brought…well, sound to the movies enhancing images in this case with machine gun fire, screams, chases through city streets and what have you that added to the realism. Worthy mentions in early “sound,” crime films are: Bryan Foy’s, The Lights of New York (1928), Rouben Mamoulian’s City Streets (1931) from a story penned by Dashiell Hammett, which was (reportedly) Al Capone’s favorite film, and Tay Garnett’s, Bad Company (1931), which was the first picture to feature the St. Valentine’s Day massacre, an event that would be depicted in many films through the years.

True events like Prohibition (until 1933), subsequent bootlegging, the existence of real-life gangsters and real crime reported in newspapers helped to encourage the crime genre. In fact, many of the sensationalist plots of early gangster films were  penned from newspaper headlines. The “rackets” of bootlegging, gambling and prostitution brought these mobsters to folk hero status, and audiences during that time vicariously participated in the gangster’s rise to power and wealth – on the big screen and sometimes in real life.

penned from newspaper headlines. The “rackets” of bootlegging, gambling and prostitution brought these mobsters to folk hero status, and audiences during that time vicariously participated in the gangster’s rise to power and wealth – on the big screen and sometimes in real life.

The movies flaunted the archetypal exploits of swaggering, cruel, wily, tough, and law-defying urban gangsters. This is particularly true of the pre-code era – that is, before the Motion Picture Production Code (aka, Hays Code or “the code”), cast its web of limitations on the movie industry. After 1934, when the code was strictly enforced, criminals and crime could not be glorified in films in any way. The clear message had to be, “crime doesn’t pay”. The code also demanded minimal details of crimes (and sex) be shown on-screen.

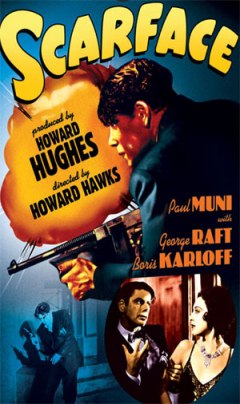

Of the early crime films, it was the Howard Hughes’ production of Howard Hawks’ raw Scarface: Shame of a Nation (1932) that had the biggest impact, both on the stricter enforcement of the code and on other crime films. This film goes “all out” in its depiction of the criminal and his crimes. The screenplay for Scarface was written by writer/journalist Ben Hecht – one he reportedly wrote in eleven days using his Chicago newspaper experiences. The original script was based on the 1930 novel, Scarface by Armitage Trail (a pseudonym for Maurice Coons) but by all accounts, the final film barely resembles the novel.

Scarface stars Paul Muni as Tony Camonte, a power-mad, vicious, and immature thug in Prohibition-Era Chicago. Muni portrays the over-the-top Camonte with exuberance and energy. The fact that this guy is ruthless and immature are conveyed beautifully. Muni can, and does, also switch to extreme menace on a dime. It’s a memorable performance.

“In this business there’s only one law you gotta follow to keep out of trouble: Do it first, do it yourself, and keep on doing it.”

Other stars are George Raft who plays Camonte’s right-hand-man, Rinaldo who is (to me) the only likeable thug in the film. Scarface made Raft a leading man and it was for this film he learned to flip a coin and does so throughout it. I mention that because in Raft’s depiction of Spats Colombo in Billy Wilder’s, Some Like It Hot (1959) he asks another gangster who is flipping a coin, “where’d you learn THAT cheap trick?” A small, but fun tidbit because it never fails to remind me of Raft in this film.

Ann Dvorak plays Tony’s sister, Cesca, Vince Barnett plays his ignoramus of a bumbling secretary (the film’s comic relief), and Boris Karloff plays Gaffney, the boss of the rival gang. Other main players will be referred to below.

The ultra-violent, landmark Scarface, includes twenty-eight deaths, although some of those are in bunches, and features (by some accounts) the first use of a machine gun by a gangster in film. The film was brought to the attention of the Hays Code for its unsympathetic portrayal of criminals, and there was an ensuing struggle over its release and content. The struggle was long and arduous and affected audience reaction and the film’s success. I’ll touch upon that a bit in the end of the post but it is a very interesting back story that’s worth reading about if you’re ever so inclined.

Rather than recounting the story told in Scarface, which is loosely based on the story of the brutal, murderous, racketeering, Al Capone, I will discuss several scenes with regard to the code and the film’s messaging to an audience. In truth, the story depicted in this film, that of the rise and fall of a criminal is not all that unique today as we’ve seen criminals rise in power and fall from grace in countless films since. But if you’re going to watch a film that tells that story, make it Scarface. Not only is it historically significant, it is also artistically impressive – still – and features fine performances across the board. Now, before I continue be warned – spoilers lie ahead in the gutter.

depicted in this film, that of the rise and fall of a criminal is not all that unique today as we’ve seen criminals rise in power and fall from grace in countless films since. But if you’re going to watch a film that tells that story, make it Scarface. Not only is it historically significant, it is also artistically impressive – still – and features fine performances across the board. Now, before I continue be warned – spoilers lie ahead in the gutter.

From the beginning – Scarface tells its story and shows its characters in a no-nonsense way. Directly and without excuse. With few exceptions, all that is shown in this film is unmistakable. Black and white. There’s little gray area offered for interpretation. When Tony Camonte is first brought in for questioning at the beginning of the film – he opens the film with a murder – we are served a close-up shot of the policeman’s shield – “the law.” And in contrast, we are shown how disrespectful and nonchalant the main character is as he lights his match right on the shield affixed to the cop’s vest. We know right off the bat Tony Camonte may be in hot water but it is of no consequence to him. He has no regard for authority although Camonte is only a small-time hood at this point, he’s as cold as they come.

And it is not only “the law” Camonte disregards, he also shows no loyalty to fellow thugs or thugs with more power. The “honor among thieves” rule is important only as long as he uses it for his own advancement. He believes and respects no one (with one exception mentioned later). To illustrate this one needs only to see how he goes for the boss’ girl, Poppy (played by Karen Morley). At first Poppy resists Tony’s advancements, she’s cautious although intrigued, because Johnny Lovo (played by Osgood Perkins) is the guy in charge after the first boss is murdered. And to “make it” as a boss in those circles you know you’re a badass! But Tony’s already making his mark at this point. Camonte was the one who killed the previous boss – right before he goes to the barbershop. Cold! But it earns him major points in crime circles and his attitude reflects he’s not afraid of anything or anyone. This is not a subtle guy whether in crime or romance – “I like Johnny, but I like you more,” he tells Poppy and a few moments later, while showing her the material he plans to use for new ties says, “and here it is” referring to his bed. The censors must have missed that little “insinuation.” Anyway, this guy feels he’s not only above the laws of society, but also above the laws within the life he’s chosen.

As the story progresses Camonte grows colder and colder and becomes more removed from society and its expectations. We see him go on a spree of killings, a “joy ride” using the machine gun he came across without measure, as if in an arcade. The machine gun, I think it’s referred to as a “tommy gun,” which he says is “like holding a baby.” He’s thrilled to bits about his new toy. Hawks, by the way, illustrates this guy’s blatant disregard for life and the law beautifully throughout the film – one of my favorite examples is during the “spree” when we get a quick view of a guy sitting inside a hotel reading “the funnies” get gunned down.

The only “soft side” to Tony Camonte is seen through the…um…interesting, shall we say, relationship he has with his sister, Cesca, which is infinitely more complicated than any of the other relationships he has in the film. From the beginning, we see he is stern with her and overly concerned about where she goes and who she’s with. He sometimes acts like a strict father and she reacts, in kind, like any young woman would who would like to start experiencing life. It may seem a simple case of an over-protective older brother, but Tony’s reactions toward her go well beyond that and the mother makes it clear to Cesca (and us), albeit with insinuations and through mutterings, that Tony doesn’t love her as a brother should.

As time passes it becomes clear that Cesca is the only thing that Tony sees as pure and clean, and the only thing he loves that is not a part of the crime-filled world he lives in. She’s not been touched by murder and lies. Although I never start this film believing their relationship is inappropriate per say, although I don’t see it as “normal” by any means, my doubt is quelled by the end of the film. By then there is no doubt that his feelings toward her are not “brotherly.” In fact it’s made rather clear that the reason he wants her kept clean and innocent is for his consumption. He wants no other man near her and no one to corrupt her. I am not quite sure still if he’d ever consummate that relationship if the movie were to continue or if both characters were to live, but the feelings are present.

It’s also worth mentioning that Cesca enjoys the life that Tony provides for her even given his inappropriate demands on her and the fact the money he gives her is a result of his criminal life. Her mother is constantly reminding her that Tony is evil but Cesca pays no mind. I think she enjoys the fact that he has those feelings for her because of what she gets out of him. She is young, 18 years old, but a party girl – in no way the innocent Tony wants her to be.

And, in the final scene when Tony locks himself in the apartment with Cesca we see that she also has feelings for him that go a step or two beyond what a sister should feel. Whether it’s the “excitement” of his life and world, or whether it is Tony himself, we get the sense Cesca would meet his prurient demands if it came to that. It is a “sense,” implied and not overtly stated – an important distinction for 1932, in particular.

That scene, the lockdown with Cesca leads to Tony Camonte’s final confrontation with the law – his death in the gutter, just as one of the cops foretold at the beginning of the film. Cesca now dead, the only thing he truly loved and coveted, Tony walks out and into a barrage of bullets.

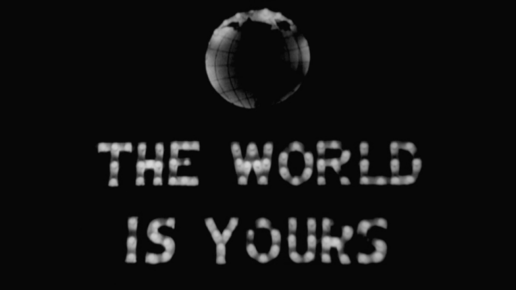

The ending I just described is a satisfying one. It is, from my perspective, a demeaning death for a criminal lost in shock, having just lost his beloved sister, succumbing to the law. But the censors didn’t see it that way. To them, that death was a glorification, a blaze of glory, solidified by Hawk’s immediate shot of a sign Camonte refers to throughout the film, his mantra, if you will, “The world is yours.”

It never occurs to me that Hawks meant that ending to be anything other than ironic. “The World is Yours,” is in direct contrast to the image of Camonte’s bullet-riddled body lying in that gutter. Clueless as they were, however, the censors demanded a new resolution to the story. Howard Hawks refused to take part in it but a new ending was shot, directed by Richard Rosson. The “new” ending is a unmistabkably moralistic one. Tony Camonte survives the final shootout to be judged and hanged by the justice system. Paul Muni was also not involved. The courtroom proceedings show only the judge denouncing Camonte and his crimes stating that, what else? “Crime doesn’t pay.” Tony Camonte is seen from a distance and in shadow, a silhouetted figure in the film’s final scene. I saw that ending in a film course I took many moons ago and must argue its effectiveness in sending the all-important, “crime doesn’t pay” message in contrast to Hawks’ original ending. Yes, I’m a little bitter.

Visuals

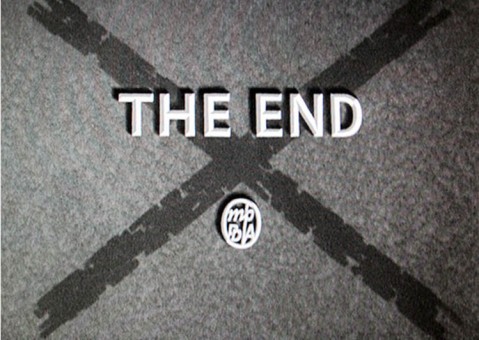

I imagine anyone watching Scarface would comment on the X motif used throughout the movie. It’s wonderfully done! For the most part I really enjoy when filmmakers “play” with the audience through visuals in such a way where there are blatant signs to be observed that have to do with the action but don’t interrupt it. What Howard Hawks did in Scarface is use Xsin all manner of ways throughout the film to mark the scenes of the crimes – either a murder that has occurred or an imminent one. I love this, I must say – it is so creative how the director injected these signs – by way of shadows, signs high up above, on a bowling sheet, a facial scar, a door number, wooden beams and even in the wall work as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre takes place when we see the seven Xs each representing a murder victim in the scene. These Xs start with the title sequence in the film – here are just a few examples:

The “X” is not the only memorable visual “tool” used by Howard Hawks in Scarface. I must give a shout out to the newspapers used throughout the film to further the story. Either via headlines or montages, newspapers are one of the tools/props used in classic film I love most. I can’t even say why but they’re just beautiful to look at and priceless as a tool for telling stories. And we see plenty of them in this film so for that alone a mention is warranted. Also, there’s one scene during the killing spree Tony Camonte goes on where Hawks uses a calendar montage to show the passing of time done with a machine gun firing in the background. Another wonderful Classic tool – the montage – used to further a story in short amount of time but in a visually compelling way. In this case it illustrates that Camonte is out of control and grows more so over time. It’s beautifully done.

There’s a lot to be said about the legacy of Scarface: Shame of a Nation. It is still noted in most fronts as “the film that defined the genre” of crime, meaning it set the standard that all crime films that followed it adhered to in one way or another. Most are also familiar with Brian De Palma’s Scarface remake in 1983, starring Al Pacino, which was meant as a tribute to Hawks’ classic. In fact, in the 2003 anniversary DVD set of De Palma’s film the 1983 version ends with a title that reads, “this film is dedicated to Ben Hecht and Howard Hawks.” Only recently, however, did I realize when reading an article on how many films were influenced by Scarface that I saw the connection made by Martin Scorsese, also in tribute to Hawks, when he used the X-motif throughout his 2006 film, The Departed. I’ve seen The Departed twice and never noticed but I took a look at it again and there they were – all over the place – Howard Hawks’ Xs! I don’t know – is it possible to love Martin Scorsese more?

OK, back to 1932 – Scarface was controversial, to put it mildly, when its release was planned and executed in 1932 not only due to its depiction of violence, but also because of its attitude toward violence. If comparing to films today, which hold little back and leave almost nothing to an audience’s imagination, I’d say the violence depicted in Scarface is not excessive. However, the attitude of Tony Camonte as the film’s main character is still quite something. The extent to which he relishes in committing crime remains unique, I think.

The Scars of the Wrath of Hays

There were many changes imposed on Howard Hawks’ original film so it could be released with the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) seal of approval, all to quell the outrage of the censors as the code reared its ugly head. One was a rewrite of the script to include Tony Camonte’s mother showing blatant disdain for her son. As a result, in almost every scene where the mother appears (played by Inez Palange) she has little to say other than, “he’s no good.” That’s one way audiences were told there was no approval of the crimes of Tony Camonte.

Another change – the “incestuous” feelings discussed above between Camonte and his sister were (reportedly) much more than insinuations in the original script. These were muted down to mere hints by Howard Hawks before the film was even reviewed because he expected outrage. His changes went uncontested leaving the film’s violence to bear the brunt of disapproval.

Another restriction is prevalent in the fact there is no blood shown despite there being so many deaths in the film. The film’s title was also changed to appease the censors – a subtitle was added to the film’s simple title, Scarface, which became Scarface: Shame of a Nation. Again, to emphasize that the film and its depictions were in no way a glorification of violence or criminals. In case that is not clear, Scarface is shameful.

One scene deserves mention as it was obviously added as an opportunity to preach to the audience – placed right, smack in the middle of the movie and it feels out of place. It is a scene between the representatives of the law and those of the media who do a back-and-forth exchange about who is to blame for glorifying the criminals and their acts. At one point, the “law” stands up and, looking straight into the camera, delivers a monologue directed at the government talking about its responsibility. In short, another iteration of what would be inserted as statements at the beginning and end of the film – as shown below. This scene was also a way to quiet some of the protest and uproar over “America’s shame” by shifting the emphasis of the story, as a repose I assume, from the criminal to the racket-busting federal agents, private detectives, or “good guys” on the other side. Whatever the reasoning, it does break up the action but not for the good – from a filmgoer’s perspective. And finally, my favorite imposition made on the film – when “the public” itself is blamed for the existence of crime through the somewhat apologetic statements added to the beginning and ending.

Apologetic but imputing of blame, that is. In essence that statement means, “the violence you are watching is your fault” so the film is presented as a mirror image of society so no one can complain about the action/violence in the film. What a great way for all involved to wash their hands of the matter. As if to say, “we made this film because you want it.” Although there is truth in that with regards to all media. But that’s another discussion.

When the Hays Code went into effect in full force in 1934, it was Scarface: Shame of a Nation that was used as an example to the public of the great good the code served. There was probably no mention of the fact the film’s release became a free-for-all as varying degrees of outrage in different states gave almost everyone free rein to show whatever version of the film they wanted – deleting scenes and dialogue and delaying showings until state boards were in agreement. Due to all the controversy and troubles associated with the film, Howard Hughes withdrew it from circulation and it remained rarely seen in the United States for almost five decades, which is a real shame as this film still packs a wallop. It is highly regarded today but it remains largely unseen. Scarface gained acceptance into the Library of Congress’ National Film Preservation Board in 1994. It is “culturally, historically and aesthetically significant.”

That’s it, you mugs.

_________________________________________________________

This is one of my entries to the Scenes of the Crime blogathon hosted by Furious Cinema, Criminal Movies, and Seetimaar – Diary of a Movie Lover. It’s a guarantee you will find enjoyment even if in the underbelly of society within the many more entries about Scenes of the Crime so go to one of the host sites and take a look around. Until you do, watch out for those Xs!

________________

A huge THANK YOU to the Classic Movie Blog Association (CMBA) for voting this article “Best Film Review (Drama) 2013” – it’s beyond thrilling.

This is one of my favorite posts from the blogathon. I love the movie and your in depth tribute to it. Just super! 😀

Thanks so much, Pete! Since you’re such a fan of this film it means a lot you liked this write-up. I mentioned – it’s a difficult one to dedicate a post to because there’s so much to say about it. But I wanted to pay it a bit of attention.

Aurora

Thanks for the great breakdown of Scarface. Of the early gangster classics it is definitely my favorite. I hope your post will interest more people in seeing this big bold movie.

Thanks so much I’m glad you liked this. I’d love that to be the case – it’s such a memorable film and definitely deserves attention. A cinematic experience STILL so many decades after it was made.

Aurora

I need to get my hands on a copy of this! I actually had no clue that the “Scarface” everyone loves was a remake. I’m not as fond of that film as everyone else seems to be, but this version looks fantastic.

Oh, yes Lindsey! You must see this. I’m not crazy about De Palm’s remake myself. While both versions are over the top, the fact that De Palma held nothing back due to the times resulted in severe overkill of the character. Anyway, let me know what you think if you are able to watch the original.

Aurora

It appears to be available on Amazon for only about $10 new or $5 used, so I’ll add it to my next DVD order! I look forward to watching it and I’ll definitely let you know what I think when I get to it. 🙂

I really need to see this one, since I’m a huge fan of crime films. I’ll publish my Scenes of the Crime blogathon post within two weeks.

Kisses!

This is a MUST see for fans of crime films. No question about it, Le.

Aurora

Brilliant review, Aurora. I loved your ending, “That’s it, you mugs.” Hee hee!

I never thought about the “X” motif before. I’ll have to keep it in mind when I see this great film again.

Thanks, R.A.! When next you see this you won’t be able to ignore the Xs!!

Aurora

Congrats on a great, thoroughly researched post! I’ve long been fascinated with the history of filmmakers’ “waltzes” with censors and other virtuous upholders of community values — in many cases, weaker films have been the result, but not always.

I had an interesting encounter with Scarface recently at the library where I work. A student came to the desk with the call number of the Muni version, of course thinking it to be the Pacino one. I suggested that both were worth a look, but of course, no sale. It’s somewhat surprising to me that De Palma’s film continues to be a cult-favorite with 20 somethings… I’ve seen Scarface action figures, mirrors, lamps — you name it!

Thanks much, Brian! Much appreciate your comments. Anything censors fascinates me as well. I happen to be of the thought that “the code” resulted in a better product over time – more creativity resulted. But, I’m not for censorship so see if that makes sense in any way.

The De Palma film’s popularity makes me scratch my head – although there is so much of it that is memorable for its extremes. I love that he did it as an homage to the original but needless to say wish people would watch Muni and that IT/HE were the more popular. It’s a tough sell with several generations.

Aurora

I just caught this movie last week from the Library and wanted to see it because I was a big fan of the 83 remake. It was cool to see a lot of parallels between the two. I also agree with you about the scene between the cops and the media. It feels out of place, and was just a moral lesson thrown in for no reason. Great post. Found your site via The LAMBcast

Thanks so much, Vern, for stopping in and your comments! So happy the LAMBcast lead you here and hope you visit again. It also makes me really happy you went out to watch this early version. I get a kick out of the similarities in story with DePalma’s film as well. It’s also interesting how they each push the envelope quite far in many ways for their respective eras.

Thanks again and hope to “see” you soon.

Aurora

Wow, this is a great post about such a classic film. I watched it originally in a film class way back in high school. I hadn’t heard of it at the time (1994) and loved it. I’ve caught it a few more times over the years, but it’s been too long. The history with the Hays Code is fascinating, particularly with Hawks giving Tony such a nasty end with “The World of Yours” in lights above him. We also watched that ending with the judge, and it’s laughable.

I was reading a book of interviews with Scorsese this week, and he mentioned the use of the “X” in The Departed. I’ve seen that movie twice and never noticed it. It seems obvious looking at the images that you showed. I definitely see a lot of Scarface in other gangster films, particularly those that show the rise and fall of a gangster. It’s a brilliant early part of the genre and deserves more acclaim. Nice work!

I’m so glad you liked this, Dan! Thanks for reading.

I love the film, as you now know, but also its history. AND the impact it had on the code. This is a MUST for all students, as far as I’m concerned.

Now you made me want to watch it yet again!

Aurora